When a brand-name drug hits the market, it doesn’t stay alone for long. Somewhere down the line, a cheaper generic version will show up. But when? That’s not just a matter of time-it’s a legal puzzle shaped by different rules in every country. The clock doesn’t start ticking when the drug is approved. It starts years earlier, when the patent is filed. And even then, the real clock-when generics can actually sell-depends on a mix of patents, data exclusivity, and government incentives that vary wildly from the U.S. to the EU to Japan.

How Long Do Patents Last? It’s Not What You Think

Most people assume patents last 20 years. That’s true on paper. The TRIPS Agreement, signed in 1995, set that global standard. But here’s the catch: drug development takes 10 to 15 years. By the time a drug gets FDA or EMA approval, there’s often only 5 to 8 years left on the patent. That’s not enough to recoup the $2.3 billion average cost to bring a new drug to market, according to Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development. That’s why countries built extensions. In the U.S., the Patent Term Extension (PTE) can add up to 5 years, but the total protected time after approval can’t go beyond 14 years. The EU uses Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs), which also cap total protection at 15 years from the date of first marketing authorization. Japan gives 8 years of data exclusivity plus 4 years of market exclusivity. Canada and the EU follow a similar 8+2 model: 8 years of data protection (no generic can use the original company’s clinical trial data), then 2 years where generics can’t even be sold, even if they’ve built their own data.The U.S. System: A Maze of Overlapping Protections

The U.S. has the most complex system. It’s not just patents. There’s also:- 5-year New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity-no generic can even file an application for five years after approval.

- 7-year orphan drug exclusivity-for rare disease drugs, even if the patent expires.

- 3-year exclusivity-for new clinical studies that aren’t just about safety or dosage.

- 6-month pediatric exclusivity-added to any existing exclusivity if the company tests the drug in kids.

- 180-day generic exclusivity-the biggest prize. The first generic company to challenge a patent and win gets a 180-day head start with no competition.

The EU and Canada: Predictable, But Slower

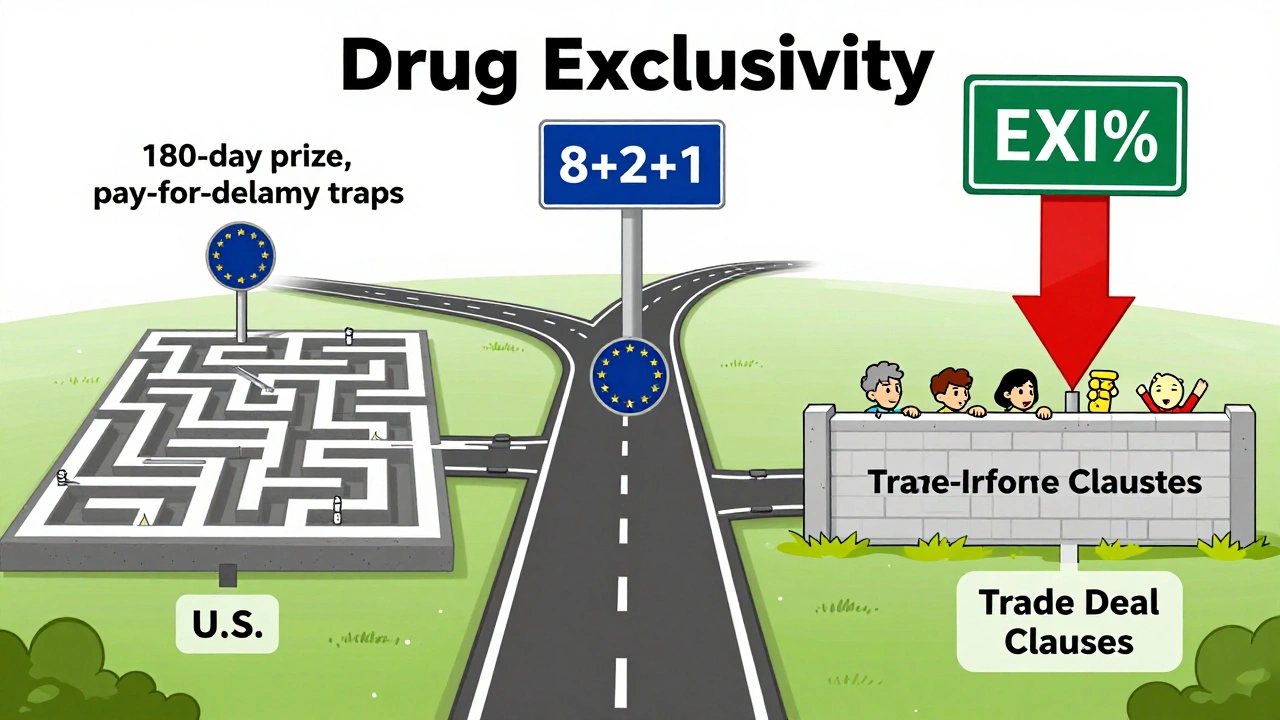

The EU doesn’t have a 180-day exclusivity period. No first-mover reward. Instead, it relies on a fixed 8+2+1 structure. Generic companies can apply for approval after 8 years, but they can’t sell until 10 years. If the original drug got a bonus for significant clinical improvements, that’s one more year. No surprises. No legal chess games. But also no big incentive for a generic company to take on a costly patent fight. Canada’s system is nearly identical. 8 years of data protection, 2 years of market exclusivity. Simple. But that simplicity means generics enter slower. In the U.S., generics can launch as soon as a patent is invalidated-even before the 5-year NCE period ends, if they challenge successfully. In the EU, they wait. Always.

Emerging Markets Are Catching Up-Sometimes Too Fast

Low-income countries often wait years longer for generics. The WHO found that essential medicines reach generic status 19.3 years after approval in low-income nations, compared to 12.7 years in rich ones. Why? Trade deals. Agreements like CETA (Canada-EU) and others include data exclusivity clauses that block generics even after patents expire. South Africa, for example, saw HIV drug generics delayed by up to 11 years because of EU trade rules. China and Brazil have been tightening their rules. China raised data exclusivity from 6 to 12 years in 2020. Brazil followed with 10 years in 2021. These moves are meant to attract big pharma investment, but they also delay access. Experts like Dr. Ellen ‘t Hoen warn that these policies hurt public health. “Data exclusivity is the new patent,” she says. “It’s harder to challenge, and it blocks generics even when patents are dead.”Why This Matters: Billions at Stake

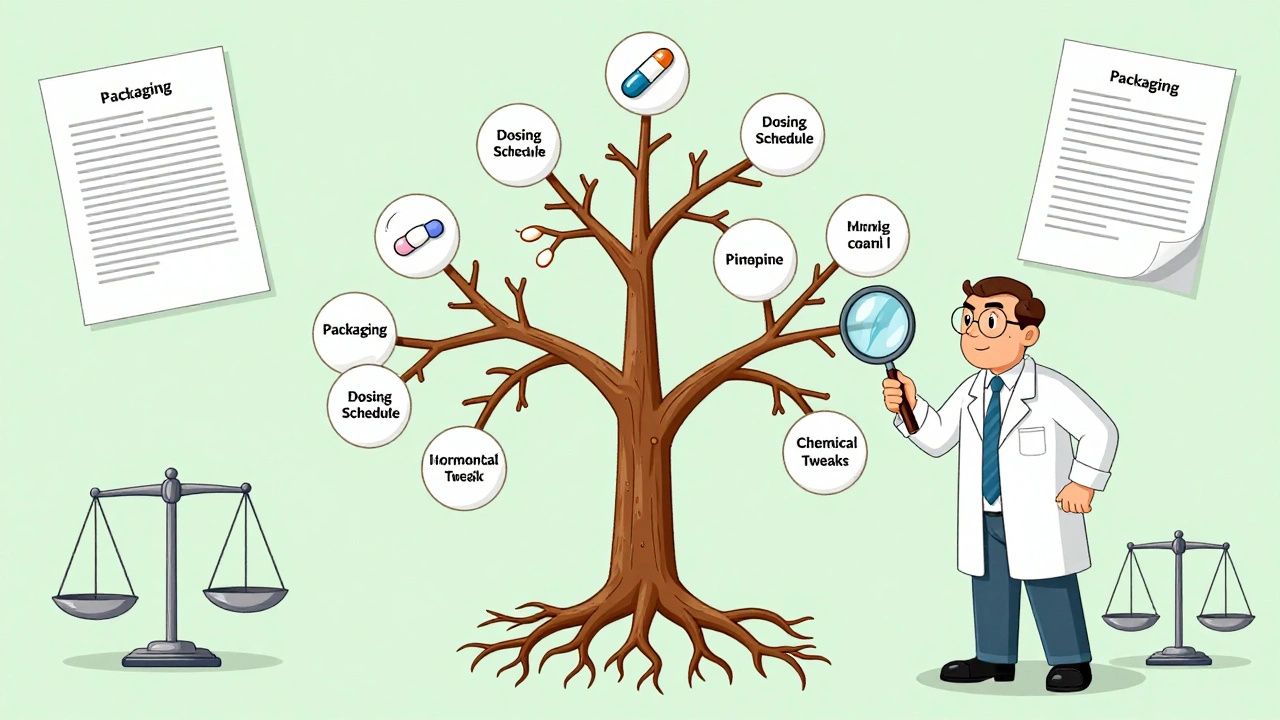

In 2023 alone, $356 billion in global branded drug sales were set to lose patent protection by 2028. That’s not just a number-it’s money for patients, pharmacies, insurers, and governments. When a generic hits, prices drop 80-90% within a year, according to IQVIA. That’s how millions can afford insulin, statins, or blood thinners. But originator companies aren’t sitting still. They file dozens of patents per drug. The top 20 pharma firms hold an average of 137 patents per product, according to LexisNexis PatentSight. These aren’t all core inventions. Many cover packaging, dosing schedules, or minor chemical tweaks-what critics call “evergreening.” Teva’s CEO said in 2023 that one brand drug can have 142 patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. Generic makers have to challenge each one, spending $2-5 million per drug just to get started. And if they lose? They’re back to square one.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

The system is designed to balance two goals: reward innovation and ensure access. But the scales are tipping. Brand companies argue they need long exclusivity. Merck says its cancer drug Keytruda’s effective market life was extended from 8.2 to 12.7 years thanks to patent stacking and exclusivity rules. That, they say, funds the next breakthrough. But critics point out that most new drugs aren’t revolutionary. A 2021 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that originator companies average 38 extra patents per drug-many on trivial changes. Dr. Aaron Kesselheim calls it “manipulation,” not innovation. Patients and pharmacists see the real cost: delays. The Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation says orphan drug exclusivity helped bring 12 new treatments since 2003. That’s good. But Health Action International found that in Africa, HIV drugs stayed expensive for over a decade past patent expiry because of data exclusivity.What’s Changing? And What’s Next?

The U.S. is trying to crack down on pay-for-delay deals. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, reintroduced in 2023, would presume such deals are anti-competitive if the payment exceeds litigation costs. The EU is proposing to shorten data exclusivity to 5 years for some drugs-but protect true innovation. Japan is streamlining its patent system to speed up generics. And the WHO is calling for a global rebalance: “Exclusivity should match actual R&D costs, not corporate profits.” One thing’s clear: the current system isn’t broken-it’s being stretched. The 180-day exclusivity, the 8+2+1 rule, the patent extensions-they all serve a purpose. But they’re also tools. And like any tool, they can be used to build access… or to block it.For patients, the question isn’t whether generics should exist. It’s when. And who gets to decide.

How long do generic drug patents last in the U.S.?

The base patent lasts 20 years from filing, but most drugs only have 6-10 years of effective protection left by approval. The U.S. allows up to 5 years of patent extension (PTE), but total protection after approval can’t exceed 14 years. Add in 5-year NCE exclusivity and other protections, and some drugs enjoy over 12 years of market exclusivity before generics can enter.

What’s the difference between patent expiry and exclusivity?

A patent protects the chemical formula. Exclusivity protects the data used to prove safety and effectiveness. Even if a patent expires, a generic can’t use the original company’s clinical trial data for 5-8 years (depending on the country). That’s why a drug can be patent-free but still have no generics-because the data exclusivity hasn’t expired.

Why does the U.S. have 180-day generic exclusivity?

It’s an incentive for generic companies to challenge weak patents. The first one to file a Paragraph IV certification (saying a patent is invalid or not infringed) gets 180 days of exclusive market access. But this system has been abused-brand companies sometimes pay generics to delay entry, which is now illegal under antitrust law.

Do all countries have the same data exclusivity rules?

No. The U.S. gives 5 years for new chemical entities. The EU and Canada give 8 years of data protection plus 2 years of market exclusivity. Japan gives 8 years of data protection and 4 years of market exclusivity. Some countries, like China and Brazil, have extended their data exclusivity to 10-12 years, which delays generic entry even after patents expire.

How do trade deals affect generic drug access?

Trade agreements like CETA or USMCA often include data exclusivity clauses that override a country’s own laws. For example, South Africa had to delay generic HIV drugs for over a decade because EU trade rules blocked generic manufacturers from using clinical data-even after patents expired. These clauses are a major barrier to affordable medicine in low-income countries.

Can a generic drug enter the market before the patent expires?

Yes-in the U.S., if a generic company successfully challenges a patent through a Paragraph IV certification. If a court rules the patent is invalid or not infringed, the generic can launch immediately. That’s how the 180-day exclusivity kicks in. In the EU, generics can’t launch until after exclusivity ends, even if the patent is invalid.

What’s the biggest obstacle for generic manufacturers?

The biggest obstacle is the legal and regulatory maze. In the U.S., companies must navigate hundreds of patents per drug, file complex certifications, and risk costly litigation. The average cost to challenge a patent is $2-5 million. Many fail because they underestimate the number of patents or miscalculate the expiry date due to overlooked extensions.

How do exclusivity periods affect drug prices?

When a generic enters, prices drop 80-90% within a year. Exclusivity delays that drop. The longer the exclusivity, the longer patients pay brand prices. In the U.S., 78% of pharmacists saw delays in generic availability in 2023 due to patent litigation or pay-for-delay deals. In low-income countries, data exclusivity can delay generics for over a decade past patent expiry.

15 Comments