Heatwaves Make Overdose Risk Much Worse - Here’s Why

When the temperature hits 24°C (75°F) or higher, the risk of overdose goes up - not just a little, but significantly. This isn’t just a theory. Data from New York City between 1990 and 2006 showed that during weeks when temperatures crossed that threshold, accidental overdose deaths spiked. The same pattern shows up in places like Philadelphia, Colorado, and even in places like Auckland, where heatwaves are becoming more frequent and intense. People who use drugs, especially stimulants like cocaine or opioids, are at much higher risk when it’s hot. Why? Because heat doesn’t just make you sweaty - it changes how your body handles drugs.

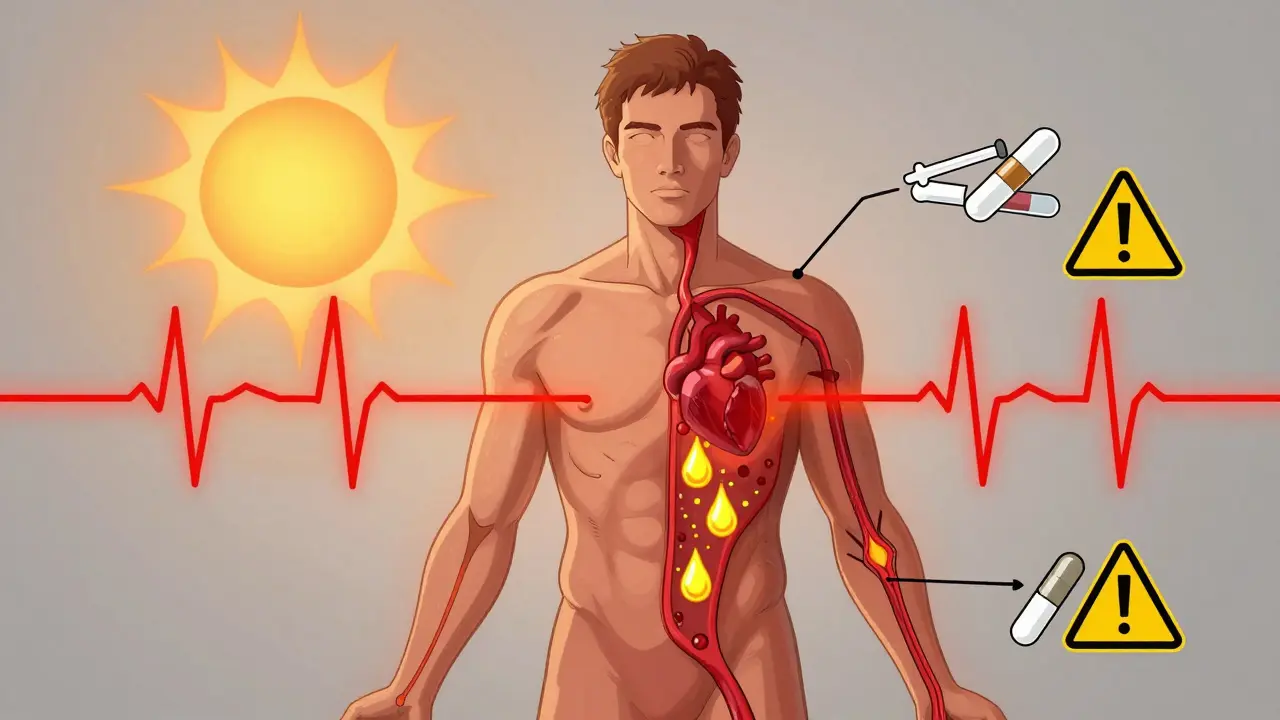

How Heat Turns a Normal Dose Into a Deadly One

When your body heats up, your heart works harder. At rest, your heart rate can jump by 10 to 25 beats per minute just from the heat alone. Now add a stimulant like cocaine, which already pushes your heart rate up 30 to 50%, and you’re putting extreme strain on your cardiovascular system. Your body can’t handle the double load. Dehydration makes it worse. Lose just 2% of your body weight in fluids - and that’s not much - and drug concentrations in your blood can rise by 15 to 20%. That means a dose you’ve used safely before can suddenly become lethal.

For opioid users, heat reduces your body’s ability to compensate for slowed breathing. Normally, your body tries to breathe faster when you’re overheated. But opioids suppress that reflex. When heat and opioids mix, your breathing can shut down faster than you can react. Studies show this respiratory compensation drops by 12 to 18% during heat exposure. Even a small increase in core body temperature - just 1.5 to 2°C - can cut your judgment and decision-making by 25 to 35%. That means you’re less likely to recognize danger, call for help, or even remember to drink water.

Who’s Most at Risk - And Why

The people most likely to die during a heatwave and overdose aren’t just those using drugs. They’re the ones who are already struggling with housing, mental health, or chronic illness. In the U.S., about 38% of people experiencing homelessness have a substance use disorder. Many of them can’t get into air-conditioned shelters because they’re turned away for using drugs. Some shelters don’t allow people who are actively using - even during a heat emergency. That forces people to stay outside, in the sun, with no water, no shade, and no way to cool down.

It’s not just homelessness. People taking medications for mental health - like antipsychotics or antidepressants - are also at higher risk. About 70% of antipsychotics and 45% of antidepressants lose effectiveness or cause worse side effects in extreme heat. These drugs can interfere with your body’s ability to sweat or regulate temperature. Add that to drug use, and you’ve got a perfect storm. In Colorado, roughly 35% of people admitted for heat-related illness also have a substance use disorder. That overlap isn’t random - it’s predictable, and it’s deadly.

What You Can Do to Lower Your Risk

If you or someone you know uses drugs, here’s what actually works during a heatwave:

- Reduce your dose and frequency by 25 to 30%. Your body doesn’t process drugs the same way when it’s hot. What was safe last week might kill you this week. Err on the side of caution.

- Drink water - regularly, not just when you’re thirsty. Aim for one cup (8 ounces) every 20 minutes. Cool water, between 50°F and 60°F, is best. Don’t wait until you feel dizzy or dry-mouthed. By then, it’s too late.

- Never use alone. Even if you’ve used before, heat changes everything. Have someone nearby who knows how to use naloxone and can call for help.

- Stay out of direct sun. Find shade. Go to a library, community center, or cooling station. If you’re homeless, ask local harm reduction groups - many now run free cooling kits with electrolyte packets, misting towels, and water.

- Check your meds. If you’re on psychiatric medication, talk to your doctor before a heatwave. Some drugs need dose adjustments when it’s hot. Don’t guess - get advice.

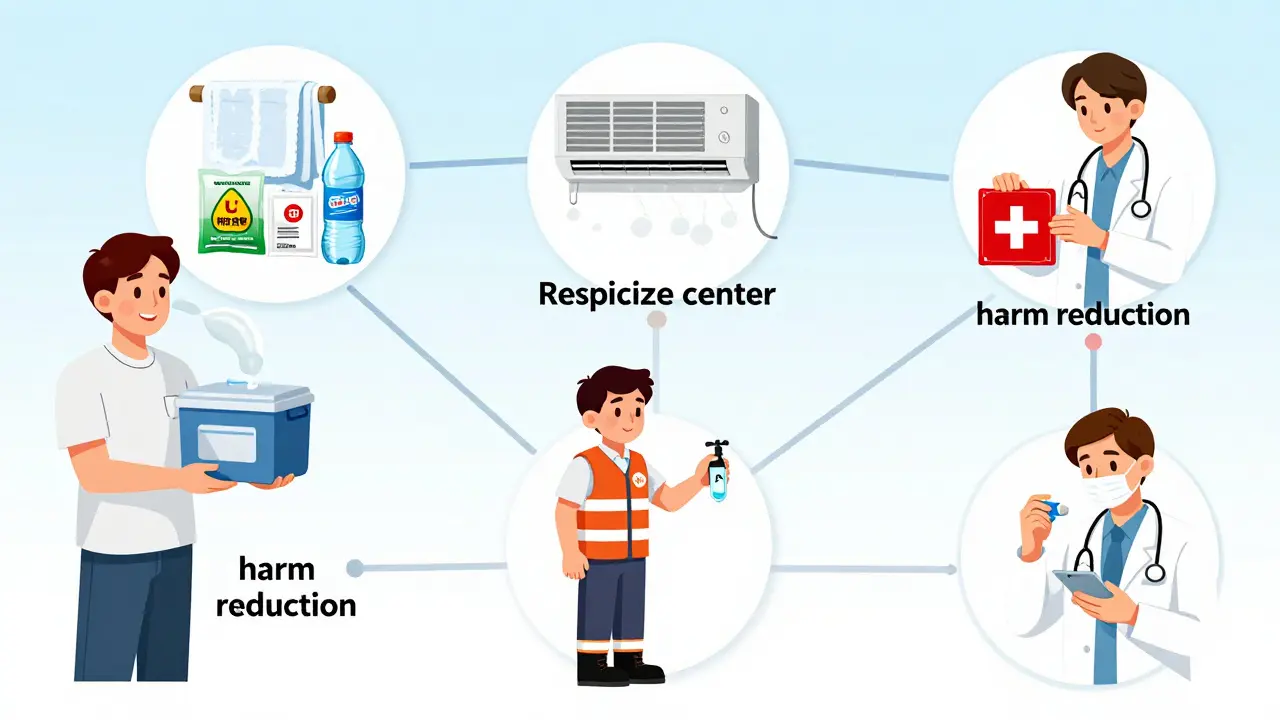

What Communities Are Doing - And What’s Still Missing

Some places are getting smarter. Philadelphia started handing out over 2,500 cooling kits each summer after their deadly 1995 heatwave. Vancouver set up seven air-conditioned respite centers next to supervised consumption sites. During the 2021 Pacific Northwest heat dome, that program cut heat-related overdose deaths by 34%. Maricopa County in Arizona trained volunteers to check on people in high-risk areas. They made over 12,000 wellness checks in one summer and intervened in 287 overdoses.

But most places aren’t doing enough. Only 12 out of 50 U.S. states include substance use in their official heat emergency plans. In many cities, police still confiscate water or cooling supplies from outreach workers. Shelters still turn people away. Harm reduction isn’t seen as part of public health - it’s treated as a nuisance. That’s changing, slowly. The Biden administration just allocated $50 million to fix this, with a deadline: all state health departments must include overdose risk in their heat plans by December 2025.

It’s Not Just About Cooling Down - It’s About Dignity

People who use drugs aren’t asking for special treatment. They’re asking not to be left to die in the heat. When you’re homeless, sick, or struggling with addiction, the last thing you need is to be told you’re not welcome in a cool room because you’re using drugs. The science is clear: heat and drug use together are deadly. The solutions exist - cooling centers, hydration stations, trained volunteers, naloxone access, and non-judgmental outreach.

What’s missing is the political will to treat this like the public health crisis it is. You don’t need a fancy program to save a life. Sometimes, all it takes is someone offering water, asking if they’re okay, and staying with them until help arrives. That’s harm reduction. That’s humanity.

What to Do If You See Someone in Distress

- Check if they’re responsive. Shake them gently and call their name.

- If they’re unresponsive, call emergency services immediately.

- If you have naloxone, administer it - even if you’re not sure it’s an opioid overdose. It won’t hurt if they didn’t use opioids.

- Move them to shade or a cooler place. Loosen clothing. Wet their skin with cool water.

- Stay with them until help arrives. Don’t leave them alone.

Heat doesn’t discriminate. But our systems do. If you’re reading this, you might be someone who uses drugs, someone who cares about someone who does, or someone who just wants to help. Whatever your role - act. Water, shade, and connection can mean the difference between life and death.

15 Comments