Drug-Induced Pancreatitis Risk Checker

Risk Assessment Result

What Is Drug-Induced Severe Pancreatitis?

Severe pancreatitis from medications is when a drug triggers dangerous inflammation of the pancreas - an organ that helps digest food and control blood sugar. Unlike pancreatitis caused by gallstones or alcohol, this form happens because of a reaction to medicine. It’s rare, making up only about 1.4% to 3.6% of all acute pancreatitis cases, but when it happens, it can be deadly. About 20% of these drug-related cases turn severe, with mortality rates between 15% and 30%. The key difference? If caught early and the medicine is stopped, your pancreas can heal. That’s not always true with alcohol or genetic causes.

Which Medications Can Cause It?

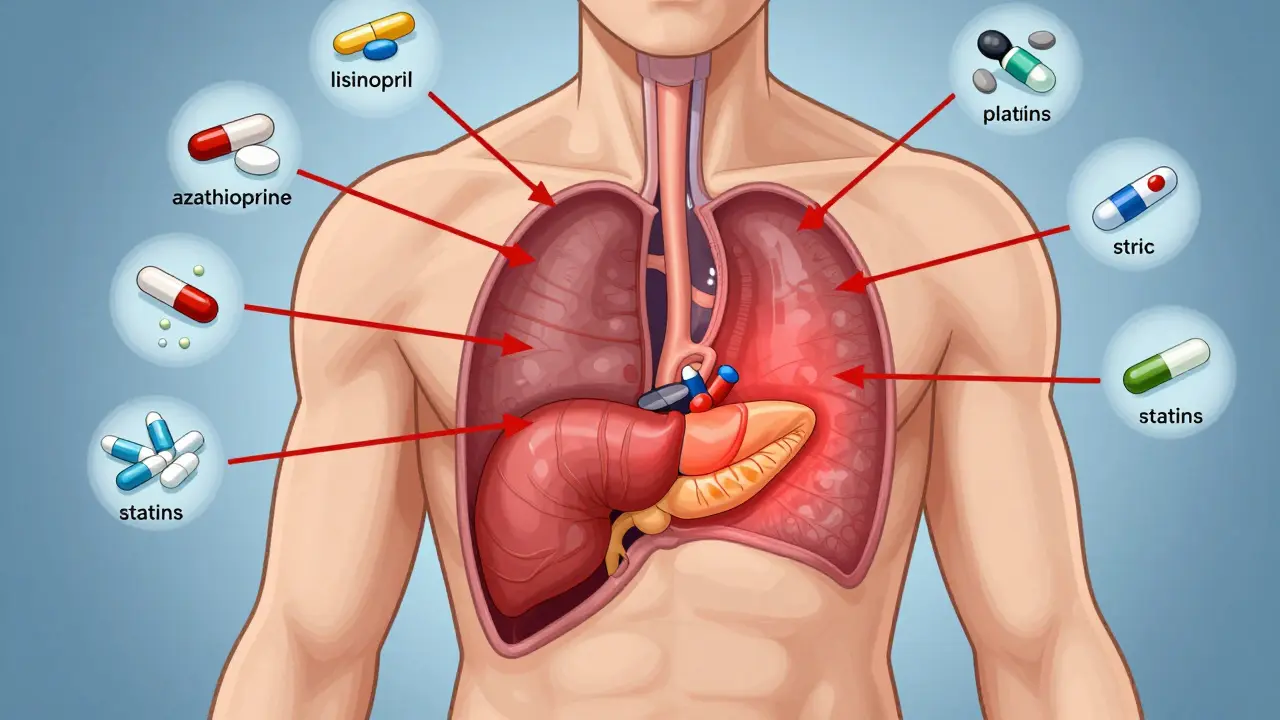

Not every drug causes pancreatitis, but eight classes have strong evidence linking them to severe cases. The most dangerous include:

- ACE inhibitors like lisinopril and enalapril - often taken for high blood pressure

- Antiretrovirals such as didanosine - used in HIV treatment

- Diuretics like furosemide and thiazides - water pills for swelling or high blood pressure

- Diabetes drugs including exenatide (Byetta) and sitagliptin (Januvia)

- Oral contraceptives with ethinyl estradiol

- Statins like simvastatin and atorvastatin - cholesterol-lowering pills

- Valproic acid - used for seizures and bipolar disorder

- Azathioprine - an immune suppressant for Crohn’s, lupus, or after transplants

Valproic acid and azathioprine carry the highest risk for necrotizing pancreatitis - where parts of the pancreas die. In some studies, up to 22% of people on valproic acid developed this life-threatening complication. Statins are tricky because they’re taken by millions. Most people never have an issue, but a small number develop sudden, severe pancreatitis after years of use. That’s why doctors now watch for new abdominal pain in long-term statin users.

Warning Signs You Can’t Ignore

Many people mistake the early signs of drug-induced pancreatitis for indigestion or a stomach bug. But there are clear red flags:

- Severe, constant pain in the upper abdomen that radiates to your back

- Pain that worsens after eating, especially fatty meals

- Nausea and vomiting that won’t go away

- Fever or rapid heartbeat

- Jaundice (yellowing of skin or eyes)

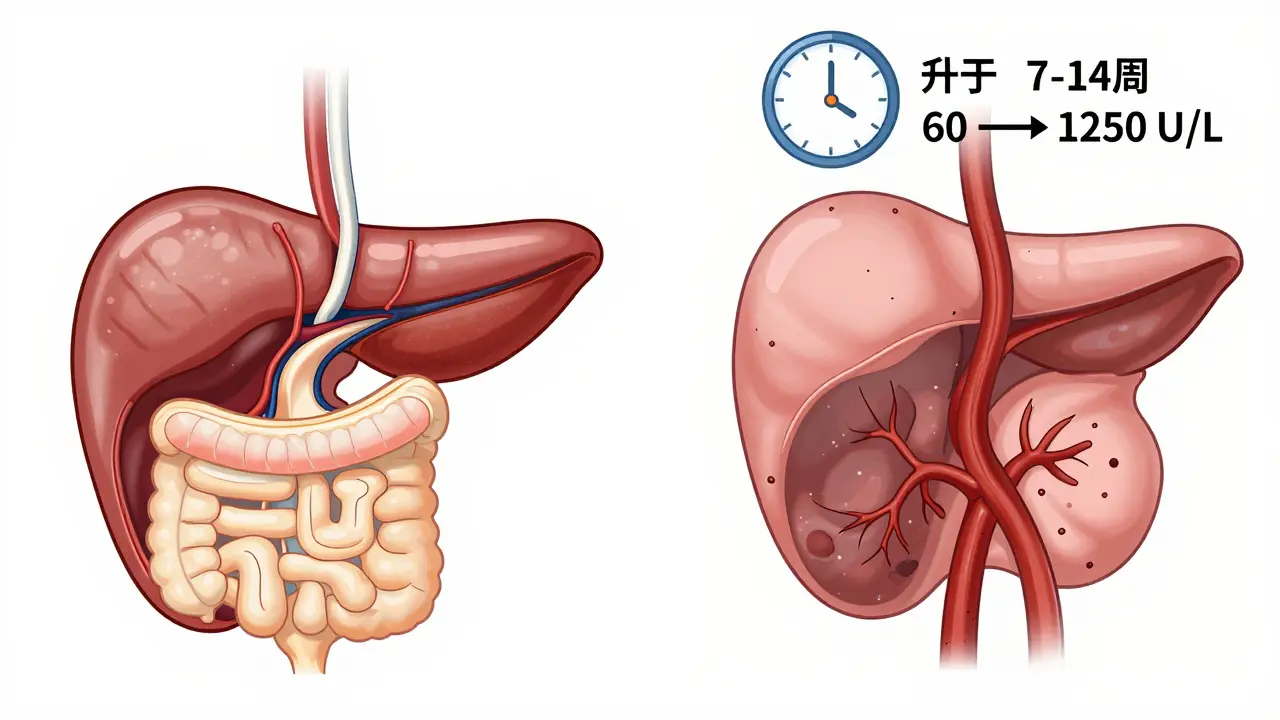

Unlike gallstone pancreatitis - which hits suddenly - drug-induced cases often creep in. Symptoms may appear 7 to 14 days after starting the medication, or even months later. One patient on lisinopril for six months woke up at 3 a.m. with pain so bad it felt like a knife in her gut. Her lipase level was over 1,250 U/L (normal is under 60). She spent five days in the hospital. After stopping the drug, she never had another episode.

Another warning sign? Delayed diagnosis. On patient forums, 68% of people with drug-induced pancreatitis say doctors dismissed their pain as "just gastritis" or "stress." If you’re on any of the high-risk meds above and have persistent upper belly pain, demand a lipase blood test. It’s more accurate than amylase for diagnosing pancreatitis.

How Doctors Diagnose It

There’s no single test that says, "This drug caused it." Diagnosis relies on three things:

- Lipase levels - at least three times above normal

- Imaging - a CT scan showing inflammation, swelling, or dead tissue (necrosis) in the pancreas

- Timing - symptoms started within 4 weeks of starting the drug and improved after stopping it

The American Gastroenterological Association calls it "probable" if symptoms match the timeline and other causes are ruled out. "Definite" requires re-challenging - taking the drug again and seeing symptoms return. But no doctor will do that on purpose. It’s too risky. So most cases are labeled "probable." Still, if your pain vanished after stopping a high-risk drug and you have no other explanation, that’s strong evidence.

What Happens in the Hospital

Severe pancreatitis is a medical emergency. Treatment starts the moment you walk in.

- IV fluids - You’ll get 250-500 mL per hour of saline to keep your blood pressure up and your pancreas perfused. Too little fluid means more tissue death.

- Pain control - Acetaminophen is first-line. If that’s not enough, low-dose morphine is given carefully. Avoid certain opioids like meperidine - they can make things worse.

- Nothing by mouth - You won’t eat or drink for the first 24-48 hours. Your pancreas needs to rest.

- Feeding tube - If you can’t eat after two days, a tube is placed through your nose into your small intestine to deliver nutrition. This cuts infection risk and speeds recovery.

- Antibiotics - Only if the pancreas tissue becomes infected. Meropenem is the go-to drug in those cases.

One critical rule: Stop the drug within 24 hours. A 2022 meta-analysis found that delaying withdrawal beyond that window increases complications by 37%. That’s not a suggestion - it’s a lifesaving step.

Why This Is Different From Other Types

Not all pancreatitis is the same.

Gallstone pancreatitis hits fast, often after a big meal, and most people improve in 72 hours. Alcohol-induced tends to come back again and again, slowly destroying the pancreas over time. But drug-induced can be a one-time event - if caught early. The scary part? Severe drug-induced pancreatitis has a higher 30-day death rate than gallstone-induced (28% vs. 18%). Why? Because patients are often on multiple meds. Treating the pancreatitis without knowing which drug caused it can lead to dangerous interactions. Also, doctors may miss the connection entirely.

One patient on azathioprine for Crohn’s disease had abdominal pain for weeks. Her rheumatologist called it "gut inflammation." By the time a CT scan was done, 40% of her pancreas was dead. She spent three weeks in the ICU. That’s the cost of delay.

What Happens After You Leave the Hospital

Recovery takes weeks - sometimes months. But here’s the good news: 65% to 75% of people who survive mild to moderate drug-induced pancreatitis recover completely after stopping the drug. No permanent damage. No lifelong meds. No surgery.

But you must avoid the offending drug forever. Re-exposure can cause another episode - often worse. Your doctor should update your medical record with a clear allergy alert: "Pancreatitis from [Drug Name]."

Some people need long-term follow-up. If your pancreas was badly damaged, you might develop diabetes or trouble digesting fat. Your doctor may prescribe enzyme supplements or monitor your blood sugar.

What’s Changing in Medicine

Doctors are getting better at spotting this. In 2023, 78% of U.S. academic hospitals added automated alerts in electronic records. If you’re on lisinopril and your lipase spikes, the system flags it. The FDA now requires stronger warnings on drugs like SGLT2 inhibitors (canagliflozin, dapagliflozin) after 87 cases were reported in just over a year.

The NIH launched the Drug-Induced Pancreatitis Registry in January 2023 to track cases and find patterns. They’re also studying genetic risks. For example, people with certain TPMT gene variants are far more likely to develop pancreatitis from azathioprine. Testing for this before starting the drug could prevent thousands of cases.

But the biggest challenge remains: awareness. Many doctors still don’t think of medication as a cause unless the patient is on something obvious like valproic acid. If you’re on any of the high-risk drugs and have unexplained belly pain - speak up. Push for testing. Your pancreas might be telling you something urgent.

Final Takeaway

Drug-induced severe pancreatitis is rare, but it’s real, dangerous, and often preventable. If you’re on any of the medications listed here and develop sudden, severe upper abdominal pain - especially if it radiates to your back - don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s heartburn. Get your lipase checked. The sooner the drug is stopped, the better your chance of full recovery. And if you’ve had it once? Never take that drug again. Your pancreas won’t survive a second hit.

11 Comments