Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis, or PSC, isn’t something most people have heard of-until it affects them. It’s a rare, progressive disease that slowly destroys the bile ducts inside and outside the liver. Bile, a fluid made by the liver to help digest fats, can’t flow properly when these ducts become scarred and narrowed. Over time, this leads to liver damage, cirrhosis, and in many cases, liver failure. There’s no cure. No magic pill. But understanding what’s happening-and what can be done-can make a real difference in how you live with it.

What Happens in Your Body With PSC?

In PSC, the immune system attacks the bile ducts. It’s not clear why, but it’s likely a mix of genes and environment. People with PSC often have a genetic fingerprint that makes them more vulnerable-especially if they carry the HLA-B*08:01 allele. That’s not something you can change, but knowing it’s there helps doctors understand your risk.

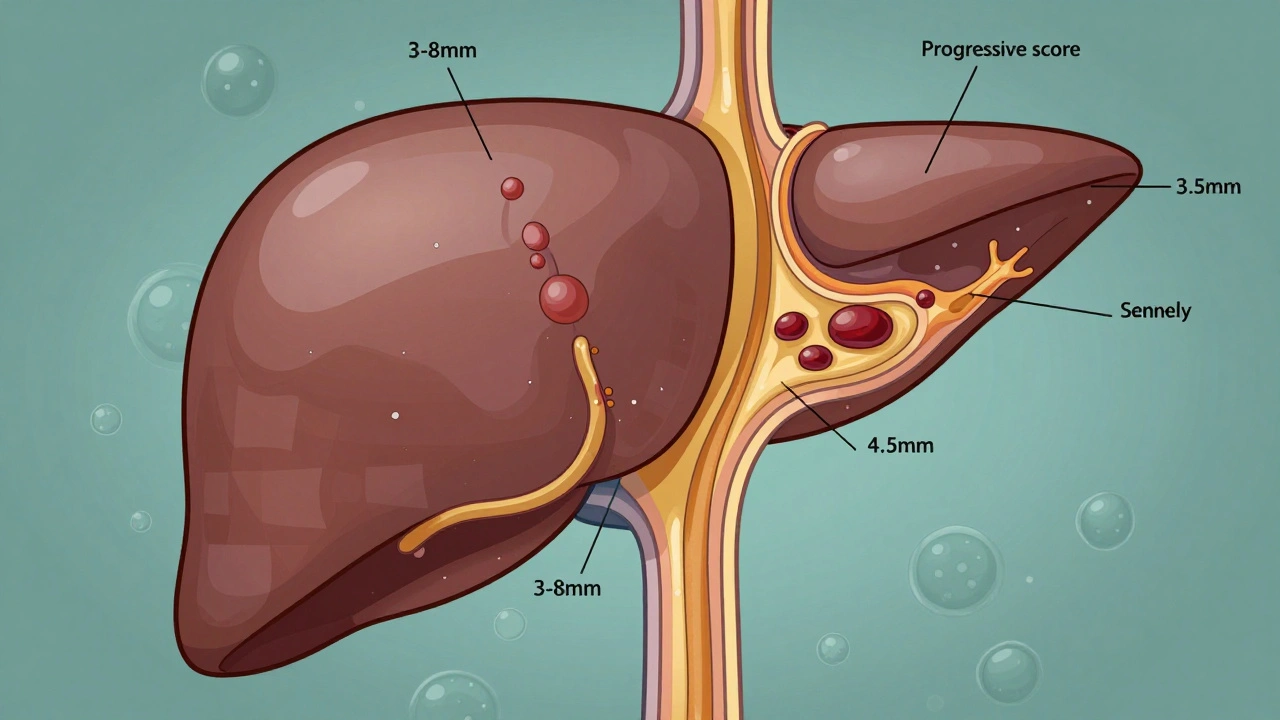

As the bile ducts get scarred, they narrow. Normal bile ducts are 3 to 8 millimeters wide. In PSC, they can shrink to less than 1.5 mm. That’s like trying to pour honey through a straw that’s half blocked. Bile backs up, damaging liver cells. Over 12 to 15 years, that damage builds up. Stage by stage, the liver goes from mild inflammation to full-blown cirrhosis. By the time someone reaches Stage 4, the liver is covered in scar tissue and can’t function properly.

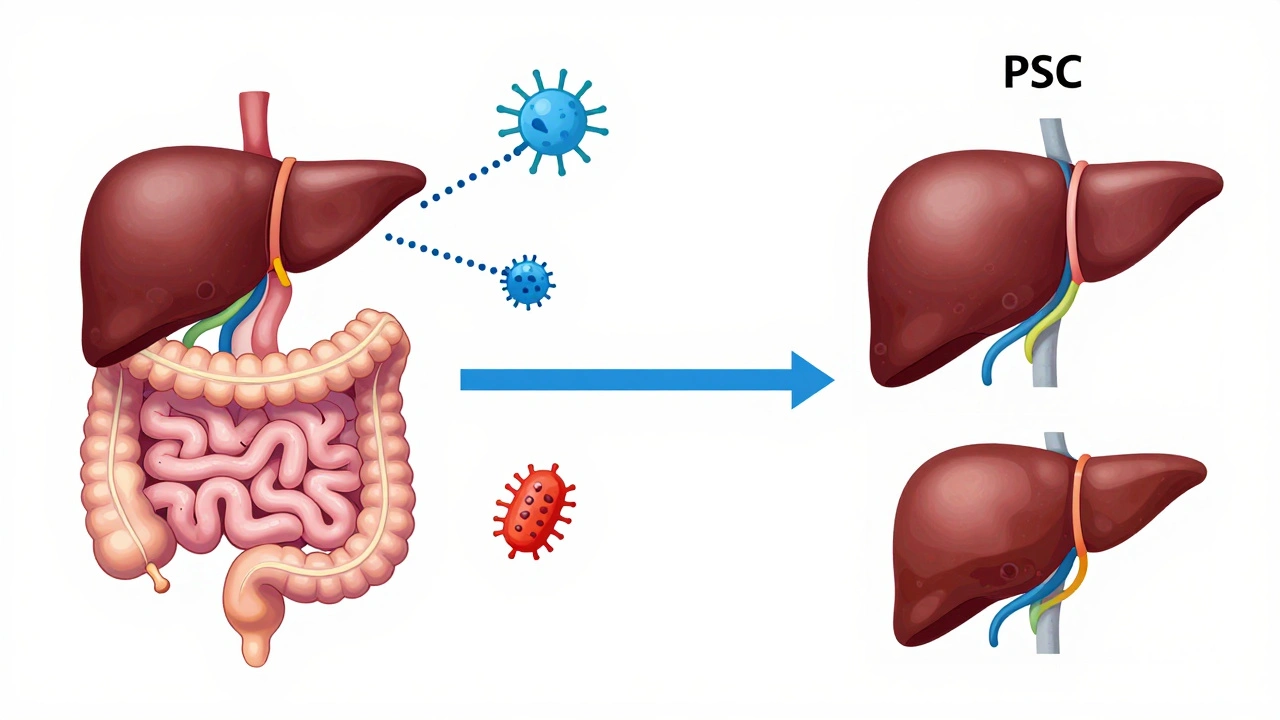

What’s unique about PSC is that it doesn’t just affect the liver-it’s tied to your gut. Around 70% of people with PSC also have inflammatory bowel disease, usually ulcerative colitis. That’s not a coincidence. Researchers now believe the gut and liver are in constant communication. When gut bacteria get out of balance, they send signals that trigger immune attacks on the bile ducts. This is called the gut-liver axis. It’s why treating PSC isn’t just about the liver-it’s about the whole system.

Who Gets PSC-and Why Is It Hard to Diagnose?

PSC mostly hits people between 30 and 50. Men are twice as likely to be diagnosed as women. It’s most common in people of Northern European descent, especially in Sweden and Norway, but it’s being recognized more in other populations too. Globally, about 1 in 100,000 people have it. In the U.S., that’s roughly 25,000 cases.

But here’s the problem: most people don’t feel sick at first. Many are diagnosed accidentally during routine blood tests that show high liver enzymes. Fatigue, itching, and mild belly discomfort are common-but they’re also common in lots of other conditions. That’s why it often takes 2 to 5 years to get a diagnosis. One patient on Reddit said, “I thought I was just stressed. Turns out my bile ducts were shutting down.”

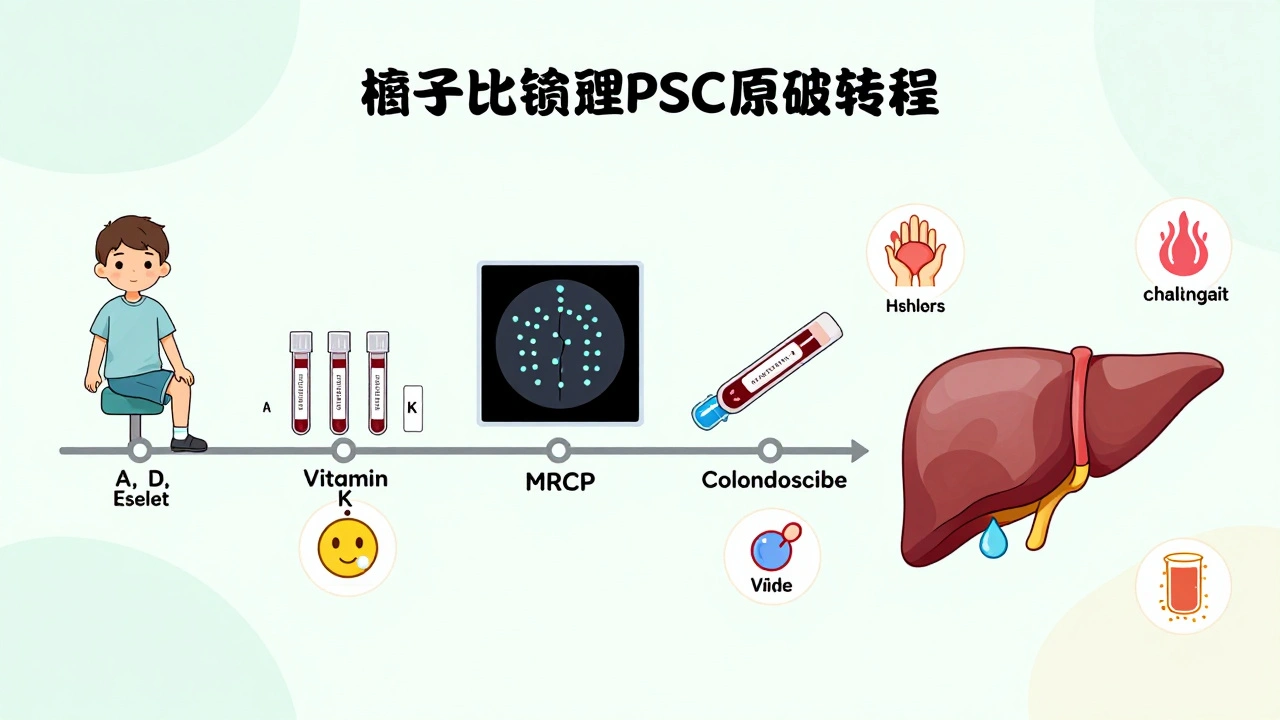

The gold standard for diagnosis is MRCP-a non-invasive MRI scan that gives detailed images of the bile ducts. If the ducts look like a “beaded string,” that’s a classic sign of PSC. In some cases, doctors use ERCP, but that’s more invasive and usually saved for when treatment is needed. Blood tests help rule out other conditions, like Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC). Unlike PBC, PSC doesn’t usually show up with anti-mitochondrial antibodies. Instead, about half of PSC patients test positive for p-ANCA, a marker that’s not specific but can support the diagnosis.

Why There’s No Drug to Cure PSC (Yet)

For decades, doctors gave patients ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) to help bile flow. It made sense. But multiple large studies showed it doesn’t improve survival or slow disease progression. In fact, high doses (28-30 mg/kg/day) might even increase the risk of complications. That’s why the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases now say: don’t use UDCA routinely.

There’s no approved drug to stop PSC from getting worse. That’s why so many patients feel frustrated. A 2023 survey found 74% of people with PSC said their doctors had “nothing to offer beyond symptom management.” It’s true. Right now, treatment is about managing what you can: itching, fatigue, vitamin deficiencies, and preventing infections.

But hope is growing. New drugs are in late-stage trials. Obeticholic acid, a bile acid receptor modulator, showed a 32% drop in liver enzymes in a 2023 trial. Cilofexor, another FXR agonist, reduced ALP levels by 41% in early testing. These aren’t cures, but they might slow the disease. The International PSC Study Group believes we could have two disease-modifying therapies approved within five years.

Living With PSC: Managing Symptoms and Preventing Complications

Living with PSC means staying ahead of problems. The biggest issues aren’t always the liver-they’re the side effects.

- Itching (pruritus): This isn’t just annoying-it’s unbearable. Some say it feels like it’s coming from inside their bones. First-line treatments include rifampicin (150-300 mg daily) and naltrexone (50 mg daily). Colesevelam, a bile acid binder, helps about half of patients.

- Fatigue: More than 90% of patients report extreme tiredness. It’s not just lack of sleep. It’s tied to inflammation and bile buildup. Exercise, good sleep hygiene, and treating underlying IBD can help.

- Vitamin deficiencies: Since bile isn’t flowing, your body can’t absorb fat-soluble vitamins: A, D, E, K. Quarterly blood tests are essential. Many patients need daily supplements.

- Cholangitis: Bacterial infections in the bile ducts can be life-threatening. Watch for fever over 38.5°C, right upper belly pain, and yellowing skin. Seek help immediately.

- Colon cancer risk: If you have PSC and ulcerative colitis, your lifetime risk of colorectal cancer is 10-15%. Colonoscopies every 1-2 years are non-negotiable.

Specialized PSC centers-like those at Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, or Oslo University Hospital-have better outcomes. A 2022 survey found 85% of patients treated at these centers reported better symptom control than those in general clinics. If you’re in the U.S., about 72% of people live within 100 miles of a PSC center. In rural Europe, that drops to 35%. Access matters.

The Long Game: Transplant and Cancer Risk

Eventually, most people with PSC will need a liver transplant. It’s the only cure for end-stage disease. The good news? Survival after transplant is excellent-over 80% of patients live five years or longer. Most return to normal life, with no signs of PSC returning in the new liver.

But there’s a dark side: cholangiocarcinoma, or bile duct cancer. About 1.5% of PSC patients develop it each year. That adds up. By 20 years after diagnosis, nearly 10-15% will have it. Once it spreads, survival drops to 10-30%. That’s why regular imaging (MRCP or CT scans) is part of long-term care. No one can predict who will get cancer, so screening is universal.

Some patients are told they’re “too healthy” for transplant right now. That’s frustrating. But transplant centers don’t operate on urgency alone-they look at overall health, function, and risk. Waiting isn’t passive. It’s about staying strong: eating well, exercising, avoiding alcohol, and managing IBD.

Where the Research Is Headed

PSC has been neglected for years. In 2022, the NIH spent $8.2 million on PSC research. For NAFLD-a much more common liver disease-they spent $142 million. That’s changing. Patient registries like PSC Partners Seeking a Cure now track over 3,100 people across 12 countries. Real-world data is helping researchers spot patterns faster.

The next big push is targeting the gut-liver axis. Probiotics, fecal transplants, and drugs that alter bile acid metabolism are all being tested. One early study showed that changing gut bacteria reduced inflammation markers in PSC patients. It’s early, but it’s promising.

By 2030, experts believe we’ll have at least two new drugs that can slow or even halt PSC progression. Until then, the focus remains on early diagnosis, aggressive symptom control, and preparing for transplant when the time comes.

Is Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis the same as Primary Biliary Cholangitis?

No. PSC and PBC are both autoimmune liver diseases, but they’re different. PSC affects both large and small bile ducts inside and outside the liver, and is strongly linked to ulcerative colitis. PBC mainly attacks the small bile ducts inside the liver and is usually diagnosed by a specific antibody called AMA (anti-mitochondrial antibody), which is present in 95% of PBC cases. PSC patients rarely have AMA, but about half test positive for p-ANCA, which is not seen in PBC.

Can you live a normal life with PSC?

Yes-many do. While PSC is progressive, it moves slowly. With good care, people live for decades. Managing symptoms like itching and fatigue, taking vitamins, getting regular scans, and staying active helps. Many continue working, traveling, and raising families. The key is early diagnosis and care at a specialized center.

Does PSC run in families?

Not usually in a clear inherited way, but genetics play a role. If you have a close relative with PSC or IBD, your risk is higher. Studies show over 20 genetic markers are linked to PSC, especially HLA-B*08:01. But having the gene doesn’t mean you’ll get the disease-it just means you’re more vulnerable if something in your environment triggers it.

Why is there no medication to cure PSC?

Because the exact trigger is still unknown. PSC is complex-it’s not just the immune system attacking the liver. It’s the gut, the bacteria, the genes, and the environment all interacting. That makes it harder to target with one drug. Most treatments tried so far only address symptoms, not the root cause. But new drugs in trials are targeting bile acid pathways and gut inflammation, and early results are encouraging.

Should I get a liver transplant if I have PSC?

Not immediately. Transplant is for when the liver is failing-when symptoms can’t be controlled, complications are severe, or cancer risk is high. Doctors use scoring systems like MELD to decide timing. Many patients wait years. The goal is to stay healthy enough for transplant when the time comes. Transplant doesn’t cure PSC’s link to IBD or cancer risk, but it replaces the damaged liver and restores quality of life.

Can diet help with PSC?

Diet won’t stop PSC, but it can help manage symptoms. A low-fat diet reduces diarrhea and bloating. Eating enough protein and calories helps prevent muscle loss. Since fat-soluble vitamins aren’t absorbed well, your doctor may recommend supplements. Avoid alcohol completely. Some patients benefit from a Mediterranean-style diet rich in vegetables, fish, and olive oil, but no specific diet has been proven to alter disease progression.

What to Do Next

If you’ve been diagnosed with PSC, find a center that specializes in it. Ask about joining a patient registry. Get your IBD checked if you haven’t already. Start tracking your symptoms-itching, energy, digestion. Keep your vitamin levels in check. Talk to your doctor about what’s coming next: imaging, blood work, and when to consider transplant.

If you’re not diagnosed but have unexplained fatigue, itching, or IBD, ask for liver tests. Don’t wait. Early detection gives you more time to prepare.

PSC is rare, but you’re not alone. Thousands are living with it. Research is moving faster than ever. And while the road is long, the destination-better treatments, better lives-is in sight.

12 Comments