When a pharmaceutical company gets approval for a new drug, it doesn’t just get a patent-it gets a clock. But that clock doesn’t tick alone. Under Section 505A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, the FDA can add pediatric exclusivity-a six-month extension to market protection-even if the patent itself hasn’t changed. This isn’t a patent extension. It’s a regulatory barrier. And for many drugs, it’s the only thing standing between a brand-name product and a flood of generics.

What pediatric exclusivity actually does

Pediatric exclusivity doesn’t make a patent last longer. It doesn’t change the date on the patent document. Instead, it tells the FDA: Don’t approve any generic version of this drug for six more months, even if the patent has expired or never existed in the first place. Think of it like a gate. The patent is one lock. Regulatory exclusivity is another. Pediatric exclusivity slaps on a third lock, one that only the FDA can open. And once it’s locked, no generic company can get final approval unless they clear all three. This rule was created because doctors were prescribing adult drugs to kids without knowing if they were safe or effective. Kids aren’t small adults. Their bodies process drugs differently. So Congress gave the FDA a tool: if a company studies a drug in children and proves it works, the FDA gives them six extra months of market control. It’s not charity-it’s an incentive.How it’s triggered

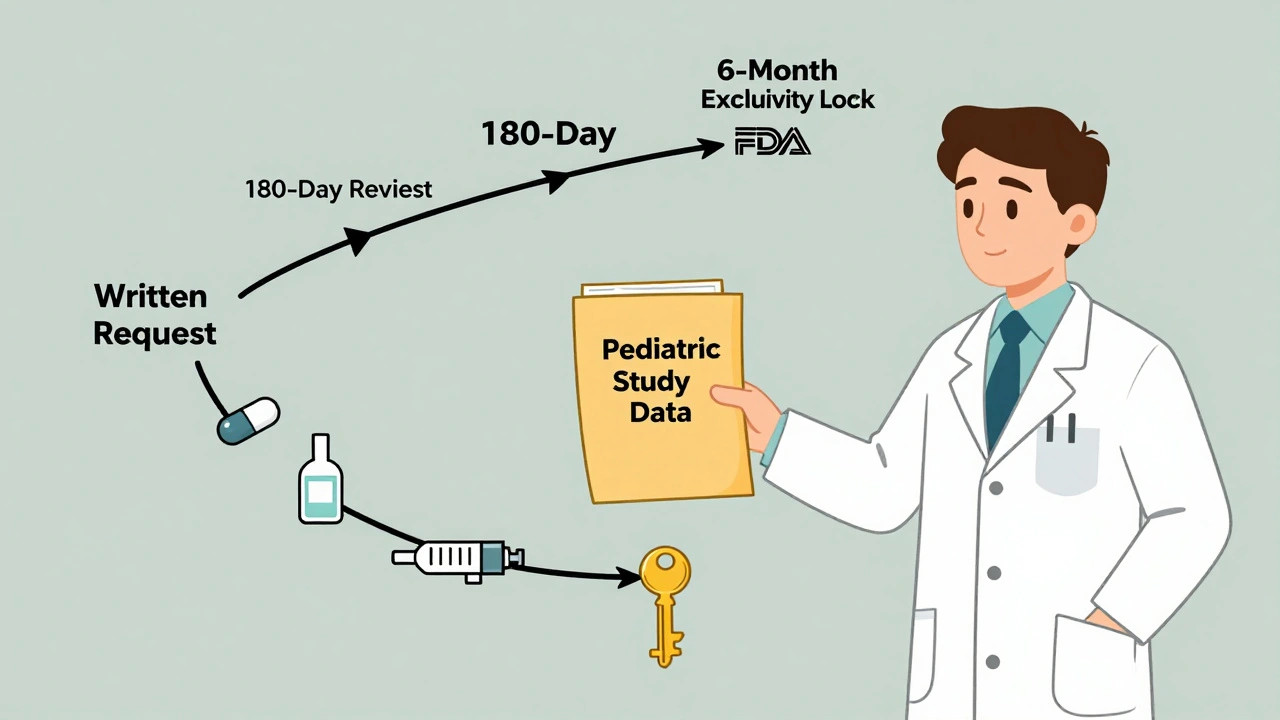

It doesn’t happen by accident. The FDA doesn’t just hand out six months to anyone who does a pediatric study. There’s a process. First, the FDA issues a Written Request. This isn’t a suggestion. It’s a formal list of studies the agency wants done-specific age groups, dosages, endpoints. The company has to agree to do them. If they don’t respond, they get nothing. Then they do the studies. Not just any studies. They have to follow the exact protocol in the Written Request. Submit the data. The FDA has 180 days to review it. If the studies are accepted, the exclusivity kicks in. And here’s the kicker: the FDA doesn’t need to approve a new label or even change the drug’s packaging. Just submitting the right data is enough. The exclusivity attaches automatically.It extends everything

Pediatric exclusivity doesn’t just attach to patents. It attaches to all existing exclusivities. If a drug has five-year new chemical entity (NCE) exclusivity? Pediatric exclusivity adds six months to that. If it’s got three-year exclusivity for new clinical data? Same thing. Even orphan drug exclusivity gets extended. But there’s a catch. The underlying exclusivity must have at least nine months left when the pediatric exclusivity is granted. If the patent expires in five months, the FDA won’t add six more. The math doesn’t work. And it doesn’t matter how many forms the drug comes in. If a company has an oral tablet, a liquid, and an injection-all with the same active ingredient-and they study the active ingredient in kids, the six-month extension applies to all forms. That’s powerful. One study, six months of protection across every version of the drug.

What happens when the patent expires?

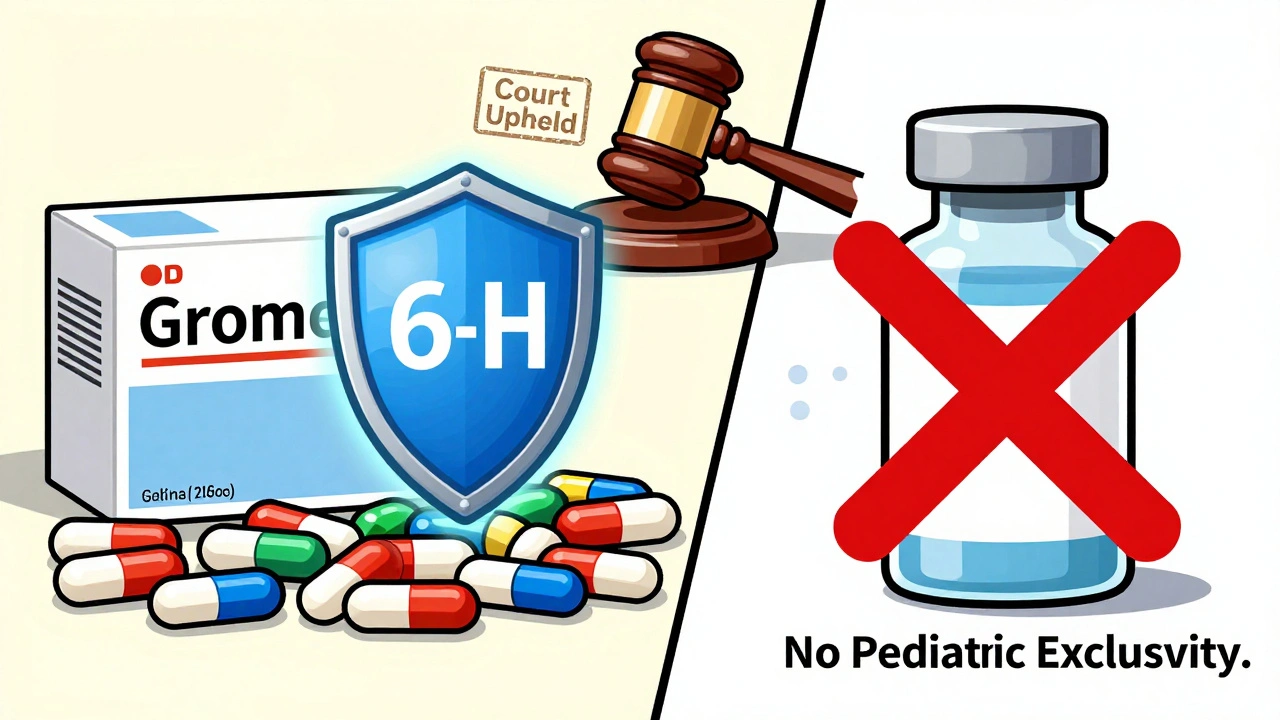

This is where most people get confused. Let’s say a drug’s patent expires on January 1, 2026. The company did the pediatric studies. The FDA grants exclusivity. Now, even though the patent is gone, the FDA still can’t approve a generic version until July 1, 2026. Generic companies file applications with Paragraph II certifications-meaning they say the patent has expired. Normally, that’s enough for approval. But pediatric exclusivity overrides that. The FDA treats it like a new barrier. Even if the patent is dead, the exclusivity lives on. Courts have backed this up. The FDA has the legal authority to convert Paragraph II certifications into de facto blocks during the exclusivity period. It’s not a loophole. It’s the law.Who can’t use it

Pediatric exclusivity doesn’t apply to everything. Biologics? No. The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) doesn’t give the FDA the same control over biosimilars that it has over small-molecule generics. So even if a biologic company does pediatric studies, they don’t get the six-month extension. And if a drug has zero exclusivity left-no patent, no NCE, no orphan status-and no pending application? The FDA won’t grant pediatric exclusivity. Unless… There’s one exception. If a company files a supplemental application to add a new pediatric indication, and that application requires new clinical data, then pediatric exclusivity can be granted even if the original product had no protection left. It’s rare, but it happens.

8 Comments