Most people don’t feel high cholesterol. No pain. No warning. No symptoms. That’s why it’s so dangerous. By the time you notice something’s wrong-chest pain, shortness of breath, a heart attack-it’s often too late. High cholesterol, or hypercholesterolemia, isn’t just a number on a lab report. It’s a silent buildup of plaque in your arteries, slowly choking off blood flow to your heart and brain. And it’s more common than you think.

What Exactly Is Hypercholesterolemia?

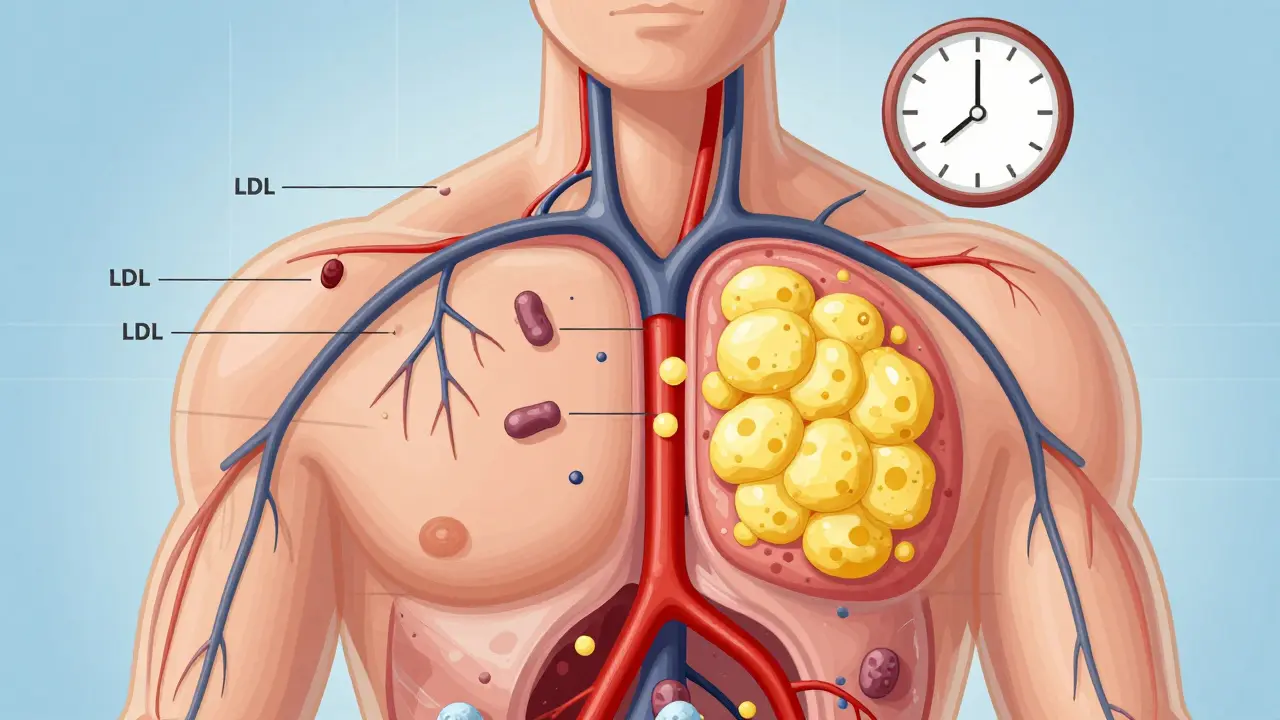

Hypercholesterolemia means your blood has too much cholesterol-specifically, too much of the bad kind: low-density lipoprotein, or LDL. Cholesterol isn’t all bad. Your body needs it to make hormones, digest food, and build cells. But when LDL levels climb too high, it sticks to artery walls, forming fatty deposits called plaques. Over time, these plaques harden and narrow your arteries. This is atherosclerosis-the root cause of heart attacks and strokes.

The American Heart Association says about 93 million American adults have total cholesterol above 200 mg/dL. That’s nearly 4 in 10 people. But numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. What matters is your LDL level. If it’s over 190 mg/dL, you have severe hypercholesterolemia. At 160-189 mg/dL with other risk factors like high blood pressure or smoking, you’re already in danger zone.

Two Types: Genetic vs. Lifestyle

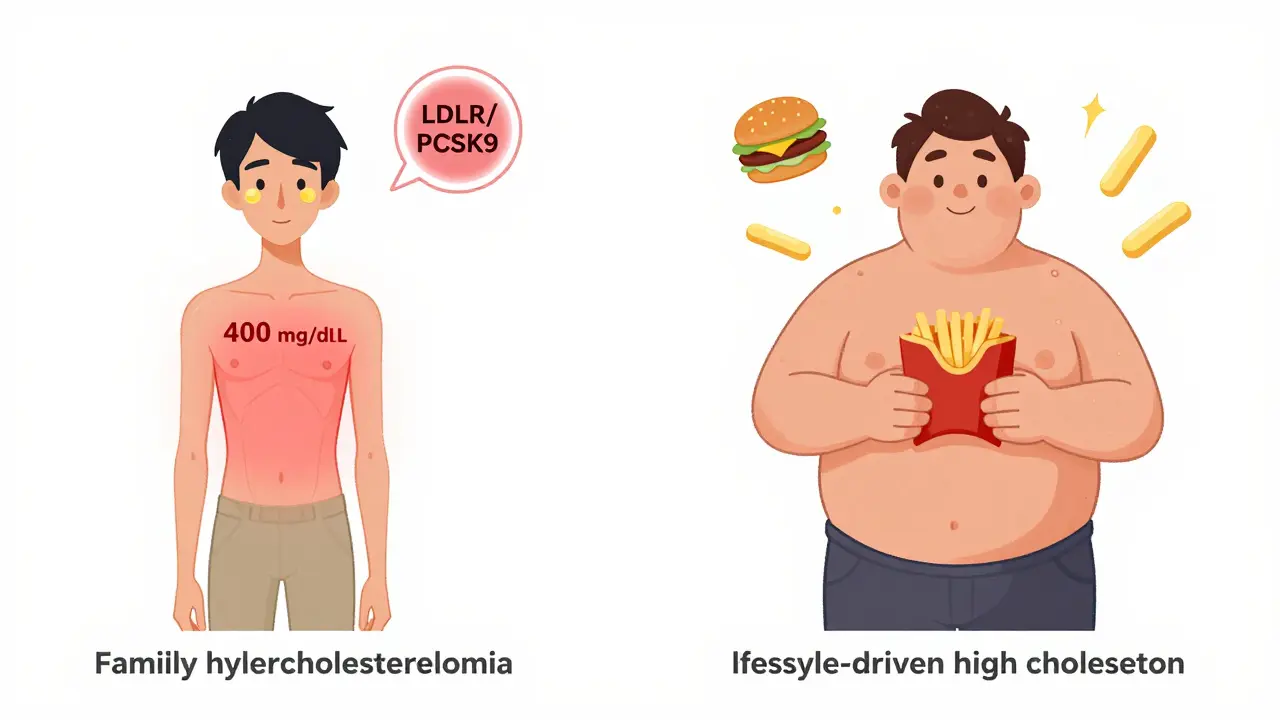

Not all high cholesterol is the same. There are two main types: familial (genetic) and acquired (lifestyle-driven).

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is inherited. You’re born with it. About 1 in 250 people globally have this condition, according to the European Atherosclerosis Society. People with FH have LDL levels often above 190 mg/dL-even as high as 400-500 mg/dL in the most severe cases. Their bodies can’t clear LDL properly because of faulty genes, usually in the LDLR or PCSK9 genes. This isn’t about eating too much butter. It’s biology. And it’s serious: untreated FH can lead to a heart attack before age 40. Some people with homozygous FH-where both parents passed on the gene-have heart attacks in their teens.

Physical signs can give FH away. Look for yellowish fatty bumps around the eyelids (xanthelasmas) or thickened tendons in the heels or knuckles (tendon xanthomas). These aren’t common in people with diet-related high cholesterol. If you or a close relative has these, get tested.

Acquired hypercholesterolemia comes from what you eat, how much you move, and other health conditions. Eating too many saturated fats (red meat, full-fat dairy, fried foods), being overweight, or having diabetes can push your LDL up. Hypothyroidism, chronic kidney disease, and even some medications like thiazide diuretics can also raise cholesterol. The good news? This type often responds well to lifestyle changes.

Why It’s Silent-and Deadly

Dr. Roger Blumenthal from Johns Hopkins puts it plainly: “High cholesterol is a silent killer-we rarely see symptoms until arteries are 70% blocked.”

By the time you feel chest tightness or pain, the damage is already done. A 2020 study in the American Journal of Cardiology showed that people with untreated FH live 30 years less on average. Men have their first heart event around age 53. Women, around 60. And those numbers don’t even include the silent strokes caused by clogged arteries in the brain.

What’s worse? Many people don’t know they have it. In the U.S., only about half of adults with high cholesterol are even diagnosed. And among those who are, only 48% are getting their LDL down to safe levels-even with statins available.

How It’s Diagnosed

You don’t need to feel sick to find out. A simple blood test called a lipid panel tells you everything: total cholesterol, LDL, HDL (the “good” kind), and triglycerides.

Here’s what the numbers mean (based on 2018 AHA/ACC guidelines):

- Optimal LDL: Less than 100 mg/dL

- Borderline high: 130-159 mg/dL

- High: 160-189 mg/dL

- Very high: 190 mg/dL or higher

And here’s a key update: fasting isn’t required anymore for most lipid panels. You can get tested anytime-no skipping breakfast. That makes screening easier, especially for busy people or those without easy access to clinics.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends everyone between 40 and 75 get checked during routine cardiovascular risk assessments. But if you have a family history of early heart disease, or if you’re overweight, diabetic, or a smoker, get tested earlier-even in your 20s.

How to Lower It-Without Just Taking Pills

For acquired high cholesterol, diet and exercise can make a huge difference. The Portfolio Diet, studied in JAMA Cardiology, showed a 10-15% drop in LDL just by eating:

- Plant sterols (found in fortified margarines)

- Soluble fiber (oats, beans, apples, psyllium)

- Nuts (a handful daily-almonds, walnuts)

- Soy protein (tofu, edamame, soy milk)

That’s not magic. It’s science. These foods block cholesterol absorption and help your liver clear LDL faster. And the results? Comparable to low-dose statins.

But here’s the catch: only 45% of people stick with the diet after a year. It’s hard to change habits. That’s why combining diet with medication often works best.

Medications: What Actually Works

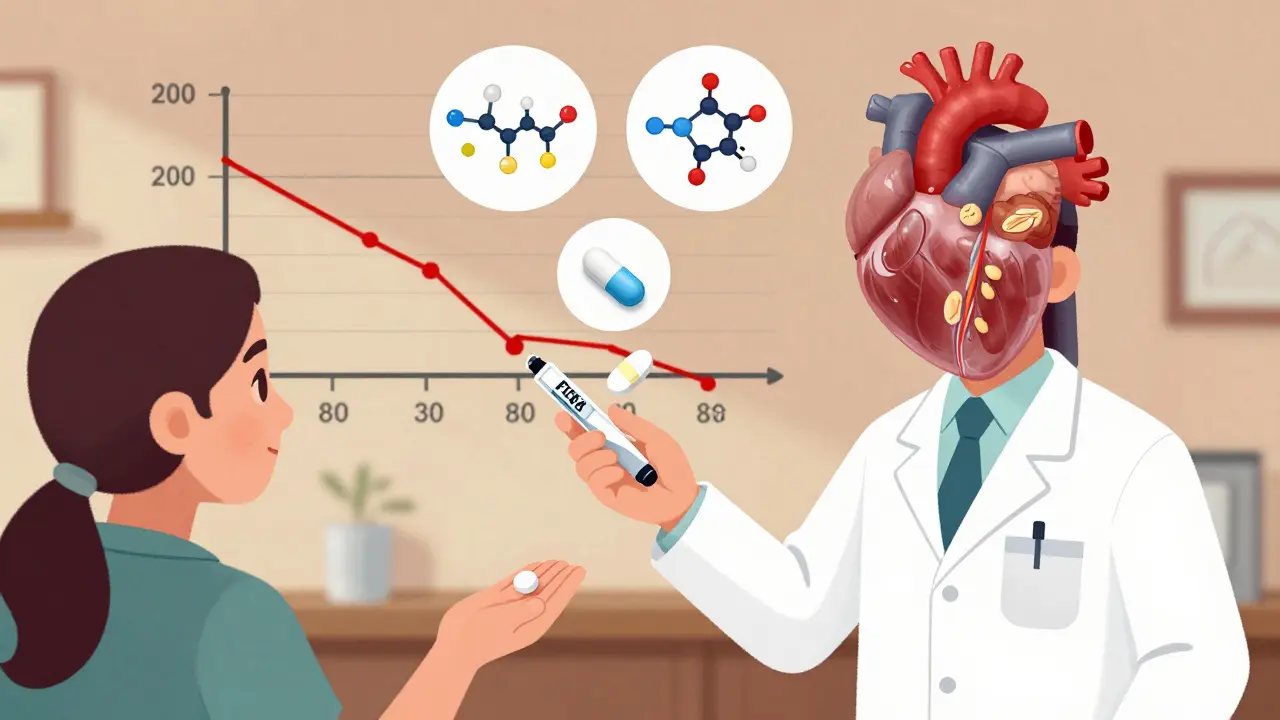

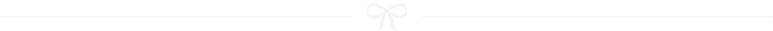

If lifestyle changes aren’t enough-or if you have FH-meds are necessary. Here’s what doctors use:

- Statins (atorvastatin, rosuvastatin): First-line treatment. They cut LDL by 30-60%. High-intensity doses (like 40-80 mg of atorvastatin) are standard for high-risk patients.

- Ezetimibe: Blocks cholesterol absorption in the gut. Lowers LDL by about 18%. Often paired with statins.

- PCSK9 inhibitors (alirocumab, evolocumab): Injectables that help the liver remove LDL. They drop LDL by 50-60% on top of statins. Used for FH or people who can’t tolerate statins.

- Inclisiran (Leqvio): A newer shot given just twice a year. It turns off the gene that makes PCSK9. It’s a game-changer for adherence-no daily pills.

For someone with familial hypercholesterolemia, triple therapy is common: a high-dose statin + ezetimibe + a PCSK9 inhibitor. That’s not overkill-it’s survival.

But here’s the problem: only about half of people taking statins stick with them after a year. Side effects like muscle pain drive people off. But before you quit, talk to your doctor. Often, switching statins or lowering the dose helps. Or adding ezetimibe lets you use a lower statin dose.

The Real Cost-Money and Lives

High cholesterol isn’t just a health issue. It’s an economic one. In the U.S., heart disease linked to high cholesterol costs $218 billion a year-$142 billion in medical bills, $76 billion in lost work.

Pharmaceutical companies made $14.3 billion selling statins in 2022, even after patents expired. PCSK9 inhibitors brought in $1.8 billion, despite costing over $5,000 a year. Many insurers won’t cover them unless you’ve tried statins first.

And disparities are stark. Black adults are 42% less likely to get statins than white adults. Women are 49% less likely than men. This isn’t just about access-it’s about awareness, bias, and systemic gaps in care.

What’s Next? The Future of Cholesterol Management

The field is moving fast. Genetic testing for polygenic risk scores can now identify people who aren’t born with FH but have dozens of small gene variants that pile up to raise cholesterol. These people need early intervention too.

And with obesity rates projected to hit 50% of U.S. adults by 2030, secondary hypercholesterolemia will keep rising. That means more people will need help-beyond pills, beyond diets.

The American Heart Association’s 2030 goal? A 20% improvement in cardiovascular health. That means better diets, more screening, digital tools to track progress, and policies that cut saturated fats from processed foods.

One thing’s clear: we can’t wait for symptoms. We need to act before the plaque forms.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you have high cholesterol and still be thin?

Yes. Weight isn’t the only factor. Genetics, diet, and underlying conditions like hypothyroidism or diabetes can raise cholesterol even in people who are lean. Someone with familial hypercholesterolemia might be skinny but have LDL levels over 300 mg/dL. That’s why blood tests matter more than appearance.

Does eating eggs raise cholesterol?

For most people, dietary cholesterol from eggs has a small effect on blood levels. What matters more is saturated fat intake-bacon, butter, fried foods. But if you have FH or diabetes, even moderate egg consumption may raise LDL. Talk to your doctor. For most, one egg a day is fine if the rest of your diet is low in saturated fat.

Can you stop taking statins once your cholesterol is normal?

No-not if you have a history of heart disease, diabetes, or familial hypercholesterolemia. Statins don’t cure high cholesterol; they manage it. Stopping them lets LDL rise again, increasing your risk of heart attack or stroke. Even if your numbers look good, the medication is still working. Always consult your doctor before making changes.

Is high cholesterol hereditary?

Yes, in some cases. Familial hypercholesterolemia is passed down in an autosomal dominant pattern-meaning if one parent has it, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting it. Even if you don’t have FH, having a parent with early heart disease (before age 55 for men, 65 for women) increases your risk. That’s why family history is part of every cholesterol assessment.

What’s the difference between HDL and LDL?

LDL (low-density lipoprotein) carries cholesterol to your arteries, where it can build up and cause blockages. That’s why it’s called “bad” cholesterol. HDL (high-density lipoprotein) picks up excess cholesterol and takes it back to the liver to be removed. That’s why it’s called “good.” But lowering LDL is the main goal-raising HDL with drugs hasn’t been shown to reduce heart attacks.

What to Do Now

If you’re over 40, get your cholesterol checked. If you’re younger but have a family history of early heart disease, diabetes, or obesity, get tested now. Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t assume you’re fine because you “eat healthy” or “look fit.”

If you’ve been diagnosed with high cholesterol, don’t panic. You have options. Start with diet and movement. Then work with your doctor. If you need meds, take them. If you’re worried about side effects, ask about alternatives. And if you have a family history, tell your relatives. They might need testing too.

High cholesterol doesn’t have to be a death sentence. But it does require action-today, not tomorrow.

14 Comments