When a new product hits the market, you’d expect it to be expensive. That’s how it’s always been - early adopters pay more, and everyone else waits for the price to fall. But something different happens with first generic entry. It’s not just a slow decline over time. The price crashes the moment the alternative arrives. And it’s not because the product is broken or inferior. It’s because the market shifts overnight.

What Is First Generic Entry?

First generic entry isn’t about a new brand coming in with a better design. It’s about someone copying the core function of a product that was once protected - by patents, by proprietary code, by high barriers to entry - and selling it for a fraction of the cost. Think of it like this: you’ve been paying $1,000 for a specific type of software because there was only one company that made it. Then, out of nowhere, another company releases the same thing. Not exactly the same. But close enough. And it costs $200. That’s first generic entry. And it doesn’t just happen in pharma - though that’s where we first saw it. It’s happening in software, electronics, and even cloud services. The moment the alternative launches, the old price structure collapses.Why Does the Price Drop So Fast?

It’s not magic. It’s math. When a product has no real competition, the seller controls the price. They can charge what they want because you have no other choice. But the second someone else offers the same thing - even if it’s not perfect - everything changes. Customers stop paying for brand loyalty. They start paying for value. In pharmaceuticals, when a patent expires and the first generic drug hits shelves, prices drop an average of 76% within six months. That’s not a guess. That’s data from the Congressional Budget Office. The same thing happens in software. When PostgreSQL became a viable alternative to Oracle, companies saw their licensing costs drop by 78%. One user on Reddit said they saved $400,000 a year just by switching. Why? Because the cost of making the copy is low. Once you’ve reverse-engineered the system, you don’t need to spend millions on R&D. You don’t need to build a sales team from scratch. You just need to offer it cheaper. And customers will rush to it.It’s Not About Quality - It’s About Perception

Here’s the surprising part: the first generic version doesn’t have to be better. It just has to be good enough. Studies show that first-gen alternatives deliver 80-90% of the original product’s functionality. That’s enough. For most businesses, they don’t need the extra bells and whistles. They need the core feature to work. And if it works at 20% of the price? They’ll switch. Take the iPod. When Apple launched it in 2001, it cost $399. A few years later, dozens of companies started making MP3 players. By 2007, you could buy one for under $50. Apple didn’t lose because their product got worse. They lost because the market decided the premium wasn’t worth it anymore. Same thing happened with TVs. Sony’s 4K model launched at $1,799 in 2015. Within a year, competitors flooded the market. The price dropped to $899. Not because Sony gave up. Because they had to.

How Do Generic Entrants Do It So Cheaply?

They don’t reinvent the wheel. They reuse it. Many first generic products rely on open-source tools, commodity hardware, and offshore development teams. Instead of building a custom database engine, they use PostgreSQL. Instead of buying expensive servers, they run on cloud instances. Instead of hiring a $200/hour engineer in Silicon Valley, they work with developers in Eastern Europe or Southeast Asia who charge a fraction of that. PwC found that software vendors using this model can cut production costs by 25-40%. That’s not a small margin. That’s the difference between a $10,000 license and a $2,000 one. And they don’t even need to be perfect. They just need to be cheaper. Many users report that switching to a generic alternative requires 20-30% more setup time. But they’re okay with that because the savings are immediate. One company told Gartner they saved $1.2 million in their first year - even after paying for migration consultants.What Happens to the Original Company?

They either adapt or get left behind. Some try to fight it. They add more features. They lock customers in with contracts. They raise support prices. But customers aren’t fooled. They know the core product hasn’t changed. All that’s changed is the price tag. The smart ones pivot. Microsoft did this with Azure SQL Database. When competitors started offering cheaper cloud databases, Microsoft shifted from upfront licenses to pay-as-you-go pricing. Their effective price dropped by 35% overnight. They didn’t lower the sticker price - they changed the model. Others, like MongoDB, offer a free tier with premium support. You can use the software for free. But if you need help, you pay. It’s a smart way to build trust before asking for money. The key insight? The power has shifted. It’s no longer the vendor who decides the price. It’s the customer.

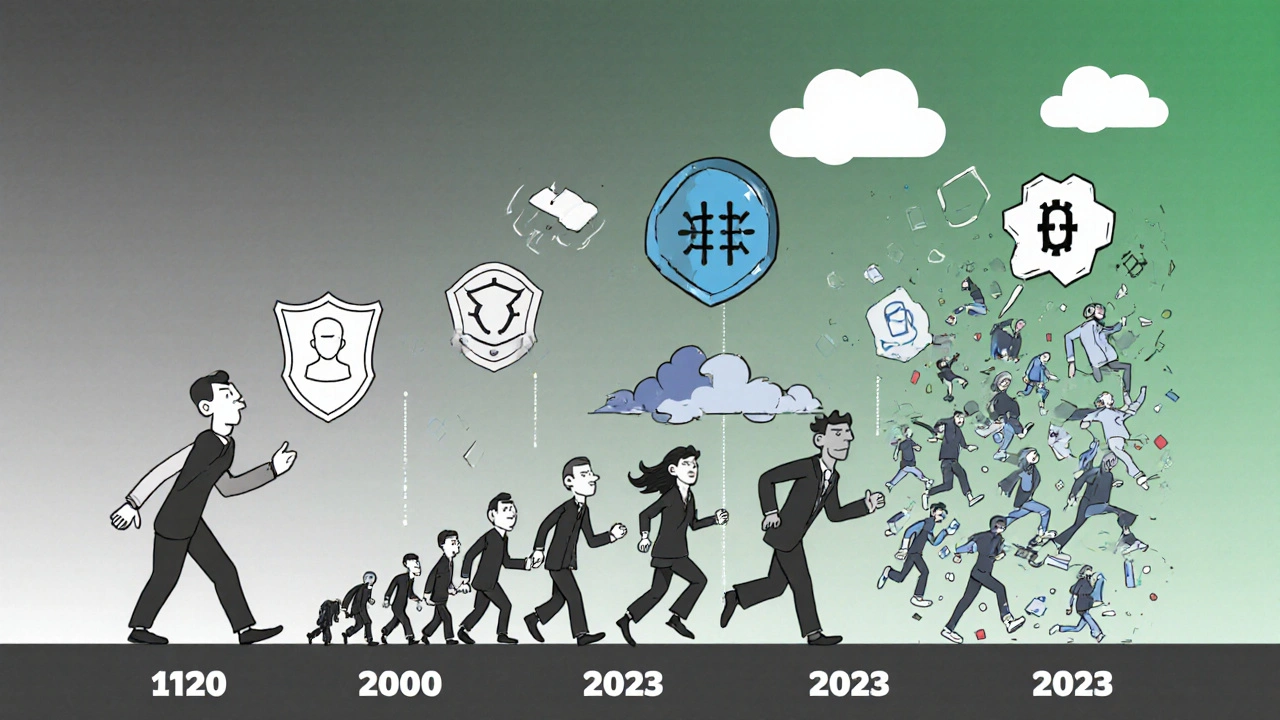

Why Now? Why Is This Happening Faster Than Ever?

Ten years ago, it took 18 months for a generic alternative to appear after a product launched. Today? It takes six months. Sometimes less. Why? Because the tools are easier. Cloud platforms. Open-source libraries. AI-assisted reverse engineering. You don’t need a team of 50 engineers to copy a system anymore. One skilled developer with the right tools can do it in weeks. Also, regulations are helping. The EU’s Digital Markets Act now forces companies to make their systems interoperable. That means switching from one product to another is no longer a nightmare. It’s a few clicks. And businesses are ready. In 2018, only 32% of Fortune 500 companies had a process to evaluate generic alternatives. By 2023, that number jumped to 67%. They’re not waiting. They’re actively looking.What Should You Do If You’re Buying or Selling?

If you’re a buyer:- Don’t wait for the price to drop. Monitor for first generic entries - they’re coming faster than ever.

- Test the alternative. Most offer free trials or open-source versions.

- Ask about support. The first-gen version might have slower response times, but that’s changing fast.

- Calculate total cost of ownership - not just the license fee. Include training, migration, and downtime.

- Stop thinking you can charge a premium forever. Your product will be copied.

- Shift from licensing to value-based pricing. Charge for outcomes, not access.

- Offer a free tier. Let customers try before they buy.

- Build community. Open-source projects with active forums outperform closed ones.

- Don’t panic. The market isn’t dying - it’s evolving.

Is This a Good Thing?

Yes. For customers, it’s a win. Lower prices. More choices. Better innovation. For vendors, it’s painful. But it forces them to stop resting on patents and start building real value. The companies that survive aren’t the ones with the best lawyers. They’re the ones with the best products. The first generic entry isn’t the end of profitable software. It’s the beginning of honest pricing.Customers aren’t paying for brand names anymore. They’re paying for results. And if you can’t deliver them at a fair price, someone else will - and they’ll do it faster than you think.

What is a first generic entry?

A first generic entry is when a competitor releases a product that matches the core functionality of an existing, often proprietary, product - usually after patents expire or through reverse engineering. This triggers immediate price drops because customers now have a cheaper alternative that works well enough.

Why do prices drop so fast after a generic product launches?

Prices drop fast because the original seller no longer has a monopoly. Once customers can get 80-90% of the same functionality at 40-80% less cost, they switch. The original vendor must lower prices or lose market share - fast.

Do generic alternatives sacrifice quality?

Not always. Many first-gen alternatives match nearly all key features of the original. The trade-off is often in support, documentation, or ease of setup - not core performance. Most users report they get what they need at a fraction of the cost.

How do companies like MongoDB and PostgreSQL compete with expensive software?

They use open-source models with freemium pricing. Offer the core product for free, then charge for advanced features, cloud hosting, or premium support. This builds trust and makes switching easy. Many users start with the free version and upgrade only when they need more.

Is it risky to switch to a first generic product?

There’s some risk - especially with early versions. Support might be slower, documentation less complete, and integration trickier. But 81% of companies that make the switch stay with the alternative after six months. The savings outweigh the headaches for most.

Will this trend keep getting worse for big software companies?

Yes. The time between a product launch and its first generic copy has dropped from 18 months in 2010 to just 6 months in 2023. Cloud tools, open-source libraries, and AI are making it easier than ever to copy software. Companies that rely on licensing alone won’t survive. Those that focus on service, support, and outcomes will.

10 Comments