Every time you take an antibiotic when you don’t need it, you’re not just helping yourself-you’re helping bacteria become stronger. That’s the harsh truth behind antibiotic resistance, a quiet crisis that’s already killing over a million people a year worldwide. It’s not science fiction. It’s happening right now, in hospitals, farms, and even your own home.

How Bacteria Outsmart Antibiotics

Antibiotics don’t kill bacteria because they’re magic bullets. They target specific weak points-like the cell wall, protein production, or DNA copying. But bacteria don’t sit still. They mutate. And when they do, those tiny changes let them survive the drugs meant to destroy them.Take ampC and pbp genes. When bacteria like E. coli or Klebsiella are exposed to amoxicillin or cefepime, these genes often change. A single mutation in ampC can make the bacteria produce an enzyme that breaks down the antibiotic before it does any damage. A mutation in pbp can alter the target site so the drug can’t latch on anymore. It’s like changing the lock so the key no longer fits.

But mutations aren’t the only trick. Bacteria also use efflux pumps-tiny molecular vacuums-that spit antibiotics out before they can work. Some bacteria even swap genes with each other like trading cards. This is called horizontal gene transfer. One resistant bug can pass its survival toolkit to another, even if they’re completely different species.

What’s scary is how fast this happens. In lab studies, bacteria exposed to low doses of antibiotics developed full resistance in as few as 150 generations. That’s weeks, not years. And here’s the twist: early resistance often comes from temporary changes in gene activity-like flipping a switch-before permanent mutations lock it in. It’s like the bacteria are testing the waters before committing.

The Real Culprits: Misuse and Overuse

You might think antibiotics are only a problem in hospitals. They’re not. The biggest driver of resistance is everyday use-often completely unnecessary.In the U.S., about 30% of outpatient antibiotic prescriptions-roughly 47 million a year-are for things that don’t need them: colds, flu, most sore throats. Antibiotics don’t work on viruses. Yet, patients ask for them. Doctors sometimes give them to avoid conflict or because they’re rushed.

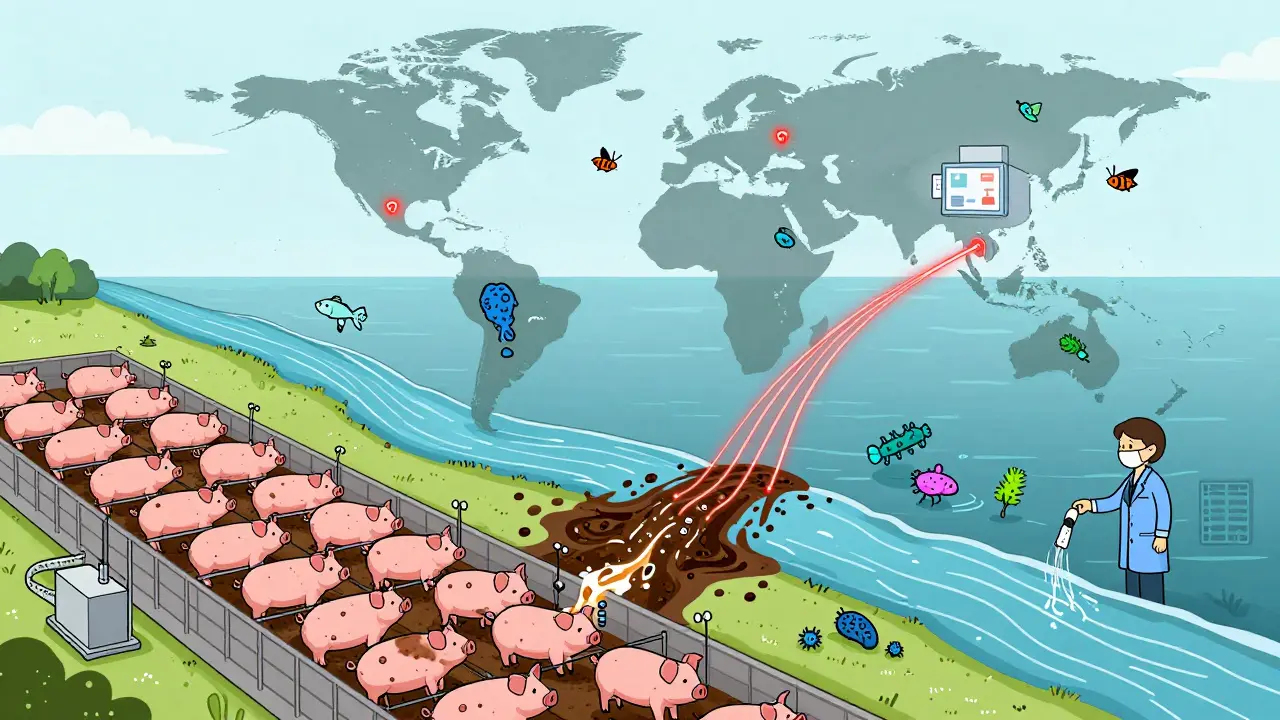

It’s even worse in agriculture. Nearly 80% of all antibiotics sold in the U.S. go to livestock-not to treat sick animals, but to make them grow faster or prevent disease in crowded, unsanitary conditions. Those drugs end up in manure, water, and soil. Resistant bacteria hitch rides on food, wind, and insects, spreading far beyond the farm.

And it’s not just antibiotics. New research shows that common painkillers, antidepressants, and even antihistamines can make it easier for bacteria to pick up resistance genes from the environment. You’re not just exposing bacteria to drugs-you’re accidentally helping them evolve.

Why This Isn’t Just a Medical Problem

Antibiotic resistance doesn’t care about borders. It’s a One Health issue-meaning human health, animal health, and environmental health are all tangled together.Think about it: a child in New Zealand gets a throat infection. She’s treated with amoxicillin. The bacteria in her gut become resistant. They’re passed to her family, then to the community. Someone else gets a urinary tract infection. The usual drug doesn’t work. They end up in the hospital. The infection spreads. A doctor has to use a last-resort antibiotic. That one starts failing too.

Meanwhile, in a factory farm overseas, pigs are fed low-dose antibiotics daily. Resistant bacteria from their guts enter the water supply. Those bacteria reach the ocean. They’re found in fish sold in Auckland supermarkets. Someone eats the fish. The resistance genes jump into their gut flora.

This isn’t hypothetical. In 2024, researchers found resistance genes in Antarctic ice cores-far from any human settlement. The resistance is everywhere.

What’s Being Done-and Why It’s Not Enough

There are efforts to fight back. Over 150 countries have national action plans. The WHO lists priority pathogens that need new drugs. Some new antibiotics are in development.But here’s the problem: of the 67 antibiotics currently in clinical trials, only 17 target the most dangerous resistant bacteria. And only three of those are truly new-designed to bypass existing resistance. The rest are old drugs with slight tweaks. They’ll likely fail too.

Antibiotic development is slow and expensive. Pharmaceutical companies don’t see the profit. Why invest millions to make a drug that’s only used for a few days, and then kept in reserve to avoid resistance?

Meanwhile, resistance testing hasn’t kept up. Doctors often guess which antibiotic to use. New tools like CRISPR-based diagnostics and AI-driven genomic analysis can predict resistance faster, but they’re still mostly in labs-not clinics.

And while antimicrobial stewardship programs in hospitals have cut inappropriate use by 20-30%, most of these programs take 12 to 18 months to show results. In the meantime, resistance keeps climbing.

What You Can Do-Right Now

You don’t need to wait for governments or drug companies to fix this. You can act today.- Don’t demand antibiotics for colds or flu. If your doctor says you don’t need them, believe them. Ask what else might help-rest, fluids, pain relievers.

- Take antibiotics exactly as prescribed. Never skip doses. Never save leftovers. Never give them to someone else. Even if you feel better, finish the full course. Stopping early lets the toughest bacteria survive and multiply.

- Ask about alternatives. For ear infections in kids, watchful waiting often works better than immediate antibiotics. For sinus infections, saline rinses and time are often enough.

- Choose meat from animals raised without routine antibiotics. Look for labels like “no antibiotics ever” or “organic.” Your dollars send a message.

- Wash your hands. Simple hygiene stops the spread of resistant bacteria before they even get a chance to cause infection.

These aren’t just good habits. They’re survival tactics.

The Future Is Still Uncertain-But Not Hopeless

Scientists are exploring wild new ideas. CRISPR systems are being designed to target and destroy resistance genes inside bacteria. Phage therapy-using viruses that eat bacteria-is making a comeback. Some researchers are even trying to block the evolution of resistance itself, by targeting the metabolic pathways bacteria use to adapt.One study found that when bacteria were exposed to antibiotics in a way that mimicked how they’re actually used in the body-intermittent doses, not constant exposure-their ability to develop resistance dropped dramatically. That means dosing schedules might be part of the solution.

But technology alone won’t save us. We need a cultural shift. Antibiotics are not candy. They’re not insurance. They’re precision tools-and like any tool, they break when misused.

The next time you’re tempted to ask for an antibiotic for a sniffle, remember: you’re not just protecting yourself. You’re protecting the next person who might need that drug to survive a simple surgery, a broken bone, or a newborn’s infection.

The antibiotics we have now are the last line of defense. Once they’re gone, modern medicine goes with them.

9 Comments