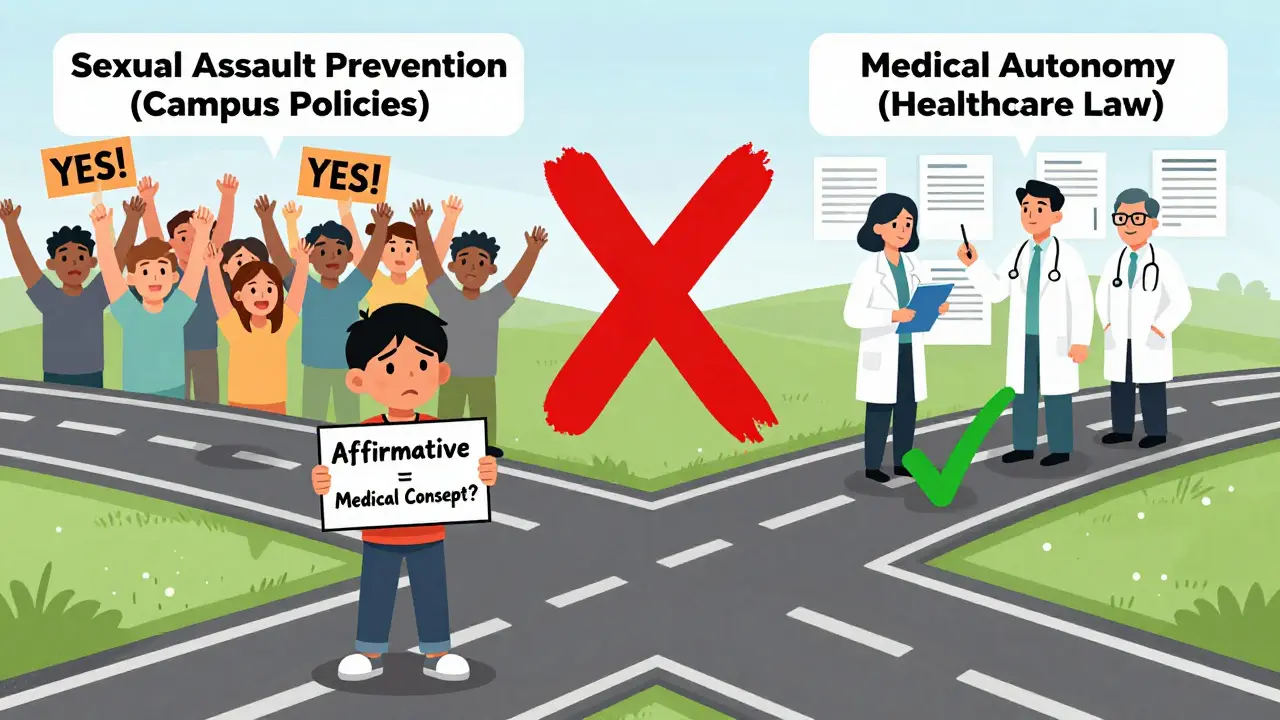

There’s a lot of confusion online about affirmative consent laws and how they relate to medical treatment. Some people think these laws-passed to combat sexual assault-also apply when a doctor needs to make a decision for a patient who can’t speak for themselves. That’s not true. And mixing these two ideas can actually hurt patients.

What Affirmative Consent Actually Means

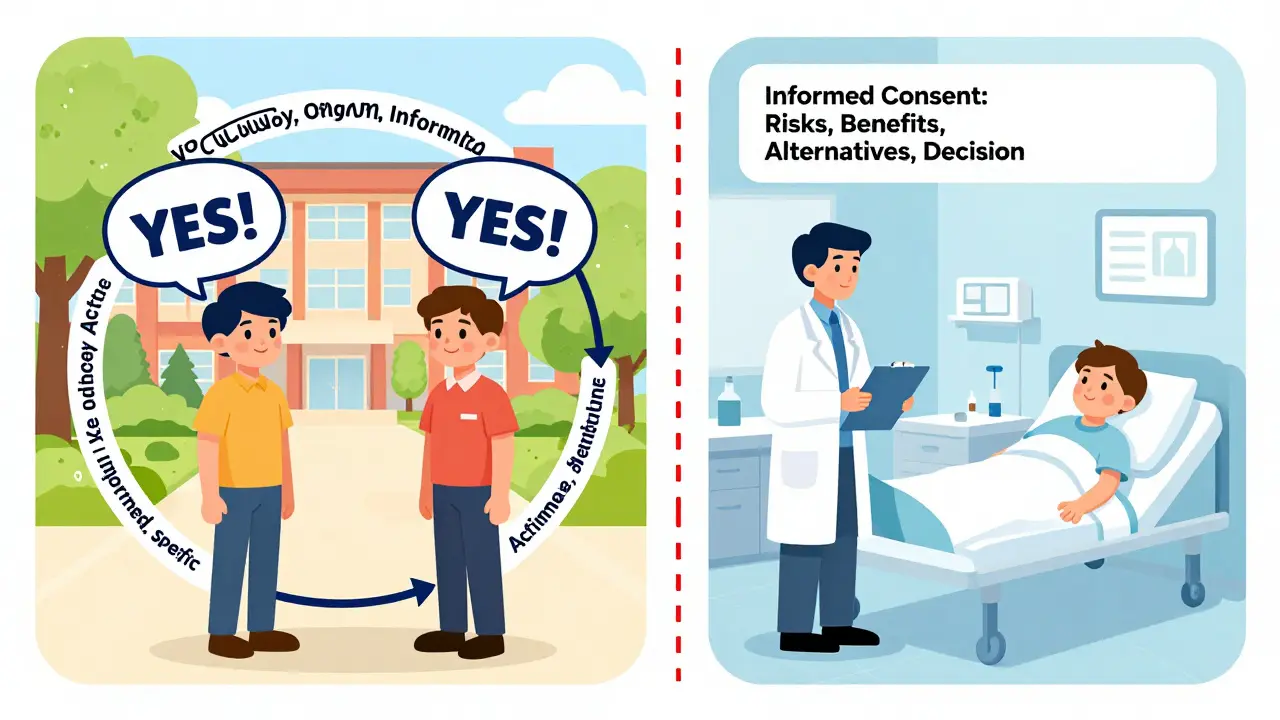

Affirmative consent laws were created to change how we talk about sexual activity. They say: no means no isn’t enough. You need a clear, enthusiastic, ongoing “yes.” This standard was first adopted in California in 2014 under Senate Bill 967, and since then, 13 states have followed suit. It’s used on college campuses, in workplace policies, and in criminal cases involving sexual assault.

The key points? Consent must be:

- Voluntary-not forced or pressured

- Active-not just the absence of a “no”

- Ongoing-can be withdrawn at any time

- Informed-both people understand what’s happening

- Specific-agreeing to one thing doesn’t mean agreeing to everything

This is about personal boundaries and power dynamics in intimate situations. It’s not about medical care.

Medical Consent Works Completely Differently

In healthcare, the legal standard is called informed consent. It’s been around for over a century, dating back to a 1914 court case where a patient sued after being operated on without permission. Since then, the rules have been clear: doctors must explain what’s wrong, what the treatment is, what the risks and benefits are, what other options exist, and what happens if you do nothing.

Then, and only then, does the patient say yes-or no. No shouting. No body language. No “maybe.” Just clear, understandable information followed by a decision.

For adults who are mentally capable, this is straightforward. But what if someone can’t decide for themselves-because they’re unconscious, in a coma, or have advanced dementia? That’s where things get tricky, and that’s probably where the confusion starts.

What Happens When a Patient Can’t Give Consent?

There’s no such thing as “affirmative consent” for medical substitution. Instead, the law uses two principles: substituted judgment and best interest standard.

Substituted judgment means the person making the decision-usually a family member or legally appointed guardian-tries to guess what the patient would have wanted, based on what they’ve said in the past. Did they refuse blood transfusions? Did they say they never wanted to be on a ventilator? That’s what matters.

If there’s no way to know what the patient would have chosen, then the best interest standard kicks in. The decision-maker picks what’s most likely to help the patient survive, recover, or avoid unnecessary suffering. No guesswork. Just medical judgment.

California Health and Safety Code Section 7185, for example, requires surrogates to use substituted judgment first. If that’s impossible, they fall back on best interest. This isn’t about getting a verbal “yes” every five minutes. It’s about respecting a person’s autonomy-even when they can’t speak.

Why the Confusion Exists

It’s easy to mix these up. Both involve the word “consent.” Both involve vulnerable people. Both are about rights. But they serve completely different purposes.

One is about preventing harm in personal relationships. The other is about protecting people’s right to control their own bodies in medical settings. They’re not interchangeable.

A 2023 survey at the University of Colorado Denver found that 78% of undergraduate students thought affirmative consent laws applied to medical decisions. That’s not just a misunderstanding-it’s dangerous. If people believe a doctor needs a patient to say “yes” out loud every time a treatment changes, they might delay life-saving care. Or worse, families might refuse treatment because they didn’t hear the right words.

Medical schools are now adding separate training modules just to untangle this. At USC, clinical staff have created workshops titled “Affirmative Consent vs. Informed Consent” to make sure future doctors don’t confuse the two.

What Happens in Real Medical Situations

Let’s say a 72-year-old woman has a stroke and can’t speak. She has no advance directive. Her daughter is her legal surrogate.

The doctor explains: “She has a blood clot in her brain. We can give her a clot-busting drug now, but it carries a 5% risk of bleeding. If we wait, the damage could be permanent. If we do nothing, she’ll likely die.”

The daughter doesn’t need to say, “Yes, I give affirmative consent.” She doesn’t need to nod. She doesn’t need to sign a form right then and there.

She says: “I know Mom said she didn’t want to be kept alive on machines. I think she’d want us to try this.”

That’s substituted judgment. It’s legal. It’s ethical. And it doesn’t require a cheerleader.

Now imagine a different scenario: a teenager comes into the ER after unprotected sex. She’s 16. In California, she can legally consent to treatment for sexually transmitted infections-even without her parents’ knowledge. That’s not affirmative consent. That’s a specific exception under California’s minor consent laws. It’s not about enthusiasm. It’s about public health.

What You Should Know as a Patient or Family Member

If you’re healthy, make an advance healthcare directive. Name someone you trust to speak for you. Write down what you do and don’t want. Don’t assume your family will know. Most don’t.

If you’re caring for someone who can’t speak, don’t panic because they didn’t say “yes.” Look for clues: past conversations, written notes, religious beliefs, even old emails. That’s your guide.

If a doctor tells you they need “affirmative consent” for treatment, ask them to explain what they mean. They might be misusing the term. You have the right to understand the legal basis for any decision made on your behalf.

The Bottom Line

Affirmative consent laws are powerful tools for preventing sexual violence. But they don’t belong in hospitals. Medical consent is built on respect, information, and legal authority-not ongoing verbal affirmation.

Confusing the two doesn’t make healthcare safer. It makes it slower, more confusing, and sometimes, less ethical. Patients deserve clarity-not a mix of two different legal systems.

If you want to protect your rights in medical situations, focus on these three things: know your options, name your proxy, and write it down. That’s how real consent works in healthcare.

9 Comments