Mountain Sickness is a form of altitude illness that occurs when the body ascends too quickly to high elevations, causing hypoxia and fluid shifts that ripple through multiple organ systems. When those shifts reach the Digestive System - the stomach, intestines, liver and pancreas - the result can be a cascade of uncomfortable, sometimes dangerous, symptoms. Below is a quick snapshot of what to expect:

- Loss of appetite and early satiety

- Nausea and frequent vomiting

- Gastric irritation or ulcer formation

- Electrolyte imbalance and dehydration

TL;DR: Rapid ascent → reduced oxygen (hypoxia) → splanchnic blood flow drops → stomach slows down, acids build, nausea spikes. Acclimatize, hydrate, eat light, and consider prophylactic meds to keep your gut happy.

Why Altitude Changes the Body’s Chemistry

The moment you cross roughly Altitude of 2,500 meters (8,200 ft), barometric pressure drops about 25%. The thinner air means less oxygen per breath, a state known as Hypoxia. Your brain reacts by increasing breathing rate, while the heart pumps faster to deliver what little oxygen is available.

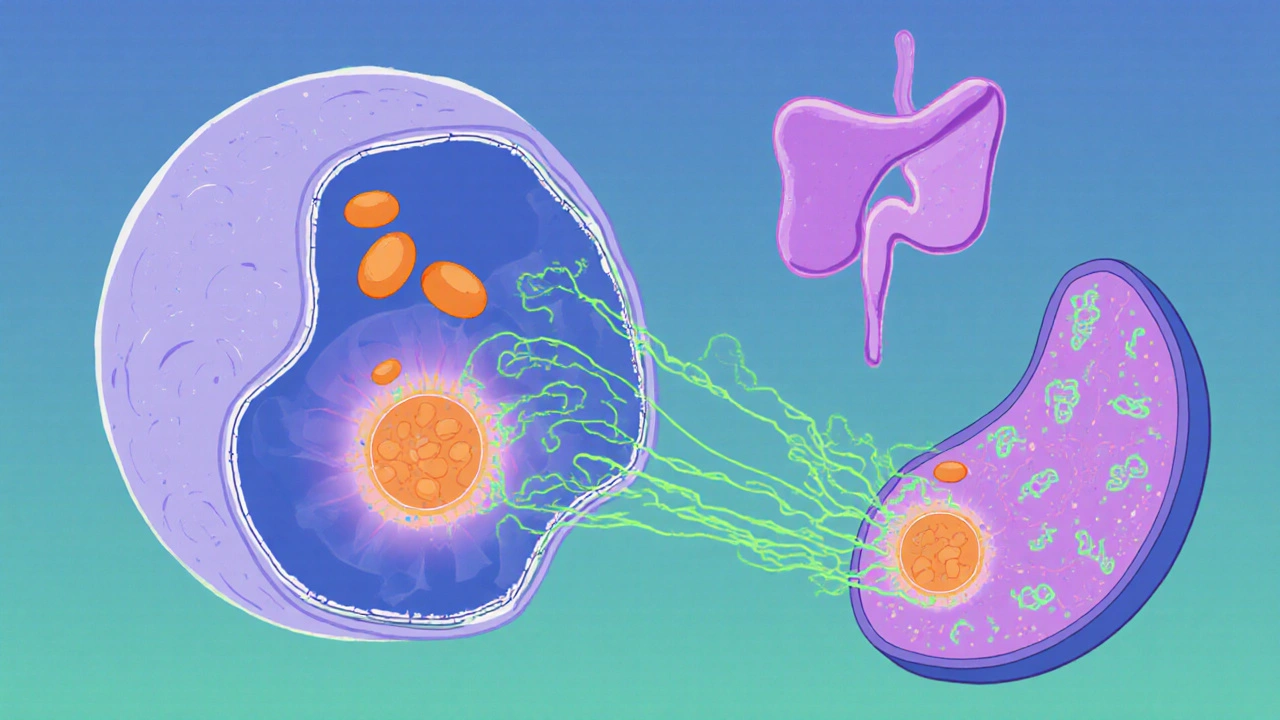

One overlooked side‑effect is the body’s effort to preserve oxygen for vital organs-brain and heart-by shunting blood away from the gut. This “splanchnic diversion” reduces digestive motility, slows gastric emptying, and irritates the stomach lining.

Specific Digestive Symptoms Linked to Mountain Sickness

Most trekkers first notice a loss of appetite. The stomach’s normal rhythm, called the migrating motor complex, stalls, leaving you feeling full after a bite or two. Nausea follows quickly because the brain’s vomiting center interprets the low oxygen as a toxin signal.

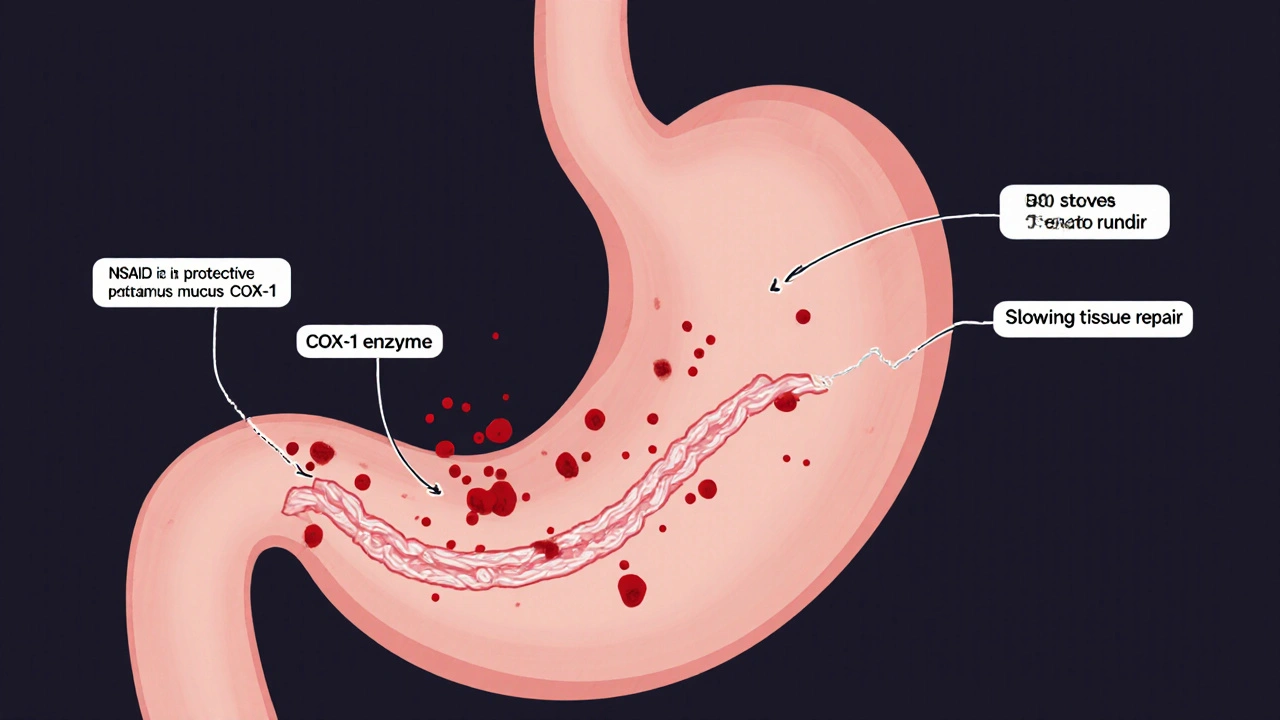

When nausea persists, the body may empty the stomach forcefully, leading to Vomiting - a protective reflex but also a cause of electrolyte loss. Repeated vomiting can erode the mucosal barrier, paving the way for Gastric ulcer formation, especially in people with a history of NSAID use or Helicobacter pylori infection.

Dehydration compounds the problem. With each breath, you lose more water through increased ventilation. Coupled with fluid loss from vomiting, electrolyte levels (sodium, potassium, magnesium) can plunge, triggering cramps, dizziness, and even cardiac arrhythmias.

Underlying Physiological Mechanisms

Three key mechanisms explain the gut’s turmoil:

- Reduced splanchnic blood flow: At high altitude, up to 30% less blood reaches the gastrointestinal tract, slowing peristalsis and impairing nutrient absorption.

- Hormonal surge: Stress hormones (cortisol, adrenaline) rise sharply, stimulating gastric acid secretion while suppressing mucus production, increasing ulcer risk.

- Altered gut microbiome: Hypoxia can shift bacterial populations, favoring strains that produce gas and exacerbating bloating.

These processes are not independent; they reinforce each other. For example, increased acid can damage the lining, prompting nausea, which then reduces food intake, further decreasing splanchnic circulation.

Risk Factors & How to Prevent Digestive Trouble

Understanding who’s most vulnerable helps you plan ahead:

- Rapid ascent: Gaining more than 300m (1,000ft) per day spikes hypoxia.

- Pre‑existing GI conditions: Ulcers, IBS, or GERD amplify symptom severity.

- High caffeine or alcohol intake: Both dehydrate and increase acid production.

Practical prevention steps:

- Acclimatize: Spend 1-2 days at intermediate elevations before pushing higher. This allows the body to increase red‑blood‑cell count and improve oxygen delivery.

- Hydrate wisely: Aim for 3-4L of water daily, adding electrolytes after any bout of vomiting.

- Eat light, frequent meals: Simple carbs (rice, oats, bananas) are easier to digest than heavy proteins or fats.

- Consider prophylactic medication: Acetazolamide reduces the severity of altitude‑related symptoms, while low‑dose proton‑pump inhibitors can protect the stomach lining if you have a ulcer history.

Probiotics, especially strains like Lactobacillus plantarum, have shown modest benefit in maintaining gut balance under hypoxic stress.

Comparison of Physiological Parameters: Sea Level vs. High Altitude

| Parameter | Sea Level | High Altitude |

|---|---|---|

| Barometric Pressure (mmHg) | 760 | ≈ 493 |

| Oxygen Saturation (SpO₂%) | 97-99 | 80-85 |

| Splanchnic Blood Flow (% of cardiac output) | ≈ 20 | ≈ 14 |

| Gastric Emptying Rate (minutes) | 30-45 | 45-70 |

| Common GI Symptoms | Occasional heartburn | Nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, ulcer risk |

The table illustrates why a stomach that works fine at sea level can feel like a ticking time bomb once you’re above 3,000m.

Managing Acute Symptoms on the Trail

If nausea strikes, the first rule is to stop eating solid food for 30minutes. Sip clear fluids-electrolyte‑rich sports drinks or oral rehydration salts-every 5-10 minutes. Small amounts of ginger tea (if you have a portable kettle) can calm the stomach.

For vomiting, administer an anti‑emetic such as ondansetron if you have a prescription, or opt for over‑the‑counter dimenhydrinate. Replace lost salts promptly; a 250ml solution containing 500mg sodium and 200mg potassium works well.

Should you develop persistent abdominal pain or suspect an ulcer, descend 500-1,000m if possible and seek medical attention. Proton‑pump inhibitors (omeprazole 20mg daily) can reduce acid output and promote healing.

Related Concepts and Next Topics to Explore

The digestive fallout from mountain sickness is part of a broader high‑altitude physiological picture. Other conditions worth investigating include:

- High‑Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) - fluid leakage into the lungs.

- High‑Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) - brain swelling that can be life‑threatening.

- Acclimatization strategies - staged climbs, “climb‑high‑sleep‑low” tactics.

When you’ve mastered the gut, the next logical step is to learn how to balance oxygen delivery with performance-a deep dive into the role of Acetazolamide as a prophylactic agent for altitude sickness.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my appetite disappear at high altitude?

Low oxygen reduces blood flow to the stomach, slowing gastric emptying. The brain also interprets hypoxia as a toxin signal, triggering loss of appetite to conserve energy.

Can I prevent ulcers while climbing?

Yes. Acclimatize slowly, avoid NSAIDs, limit caffeine/alcohol, stay hydrated, and consider a low‑dose proton‑pump inhibitor if you have a prior ulcer history.

Is ginger effective against altitude‑related nausea?

Studies on mountaineers show ginger can modestly reduce nausea by soothing the gastric mucosa. It's safe, lightweight, and worth packing.

How much water should I drink at 4,000m?

Aim for 3‑4L per day, plus extra after any vomiting. Adding electrolyte tablets helps replace salts lost through rapid breathing and sweat.

When should I descend because of digestive symptoms?

If vomiting persists for more than 12hours, you develop severe abdominal pain, or you cannot keep fluids down, descend at least 500m and seek medical help.

6 Comments