Prolactin Level Checker

Check Your Prolactin Level

Enter your prolactin level (ng/mL) to see its impact on breastfeeding.

Results

Enter a prolactin level to see analysis

Key Takeaways

- Hyperprolactinaemia is an excess of the hormone prolactin, which can both help and hinder milk production.

- Moderately elevated prolactin often supports breastfeeding, but very high levels may signal underlying disorders that disrupt lactation.

- Common causes include pituitary adenomas, certain medications, thyroid imbalance, and chronic stress.

- Diagnosis involves blood tests, imaging, and a review of symptoms such as irregular periods or galactorrhoea.

- Treatment with dopamine agonists, adjusting medications, or managing stress can restore a healthy prolactin range and improve breastfeeding outcomes.

Hyperprolactinaemia sounds scary, but the reality is nuanced. When you’re feeding a newborn, the hormone prolactin is the star that tells your breasts to make milk. Too little, and milk supply falters; too much, and the body may be signaling another health issue that can actually interfere with the lactation process.

In this guide we’ll break down what hyperprolactinaemia is, why it matters for breastfeeding mothers, how to spot warning signs, and what practical steps you can take to keep both your health and your baby’s nutrition on track.

Understanding Hyperprolactinaemia

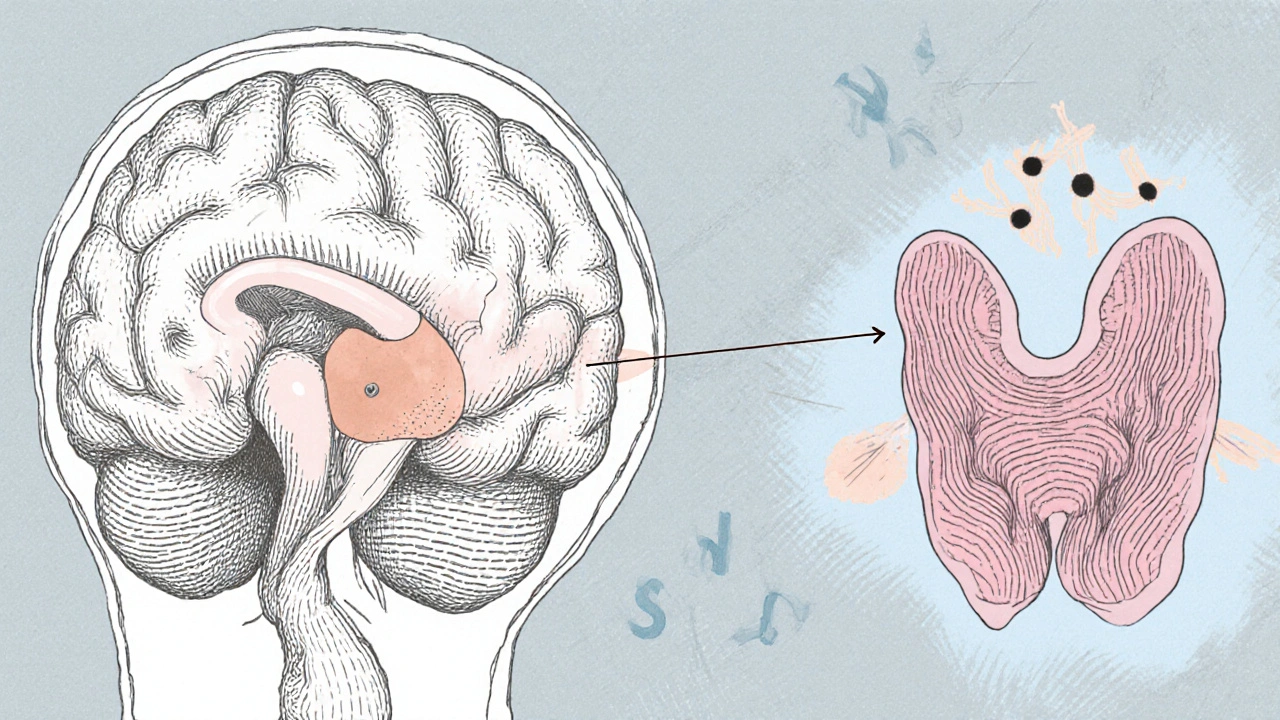

The condition is defined as a serum prolactin concentration higher than the normal range-usually above 20 ng/mL for non‑pregnant women, though the exact cut‑off can vary by lab. Prolactin is produced by the pituitary gland, a tiny pea‑sized organ at the base of the brain.

While a modest rise in prolactin is a natural response to infant suckling, marked elevations often point to one of several underlying causes:

- Pituitary adenoma (a benign tumor producing excess prolactin)

- Medications that block dopamine, such as certain antipsychotics or anti‑emetics

- Hypothyroidism - an under‑active thyroid that can stimulate prolactin release

- Chronic stress, which disrupts the dopamine-prolactin feedback loop

- Kidney disease, which impairs prolactin clearance from the blood

How Prolactin Impacts Milk Production

Prolactin’s primary job during lactation is to stimulate the alveolar cells in the breast to secrete milk. The more often the baby suckles, the more prolactin the pituitary releases-a classic supply‑and‑demand system.

When prolactin levels are within the optimal window (roughly 40‑100 ng/mL during active breastfeeding), milk supply is usually robust. However, once the hormone climbs well beyond that-say, above 200 ng/mL-two things can happen:

- Milk synthesis may become erratic, leading to "spitting up" or inconsistent flow.

- Other hormonal pathways, like oxytocin release, may be suppressed, reducing the milk ejection reflex.

These effects are why some mothers with severe hyperprolactinaemia experience lactation failure despite frequent feeding.

Spotting the Signs: When to Get Tested

Typical early clues include:

- Unexpected milk over‑production followed by sudden drop‑off

- Persistent breast engorgement or leaking outside feeding times

- Irregular menstrual cycles or amenorrhea after delivery

- Galactorrhoea (milk discharge unrelated to feeding) in the absence of a baby

- Headaches or visual disturbances, which may hint at a pituitary mass

If you notice any of these, a simple blood test measuring serum prolactin can confirm whether hyperprolactinaemia is at play. Doctors often follow up with an MRI of the brain to rule out a pituitary adenoma.

Managing Hyperprolactinaemia While Breastfeeding

Fortunately, most causes are treatable, and many interventions are compatible with continued nursing.

Medication Adjustments

If a prescribed drug is the culprit, your clinician may switch you to a prolactin‑neutral alternative. For example, tricyclic antidepressants can sometimes be replaced with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors that have less impact on dopamine pathways.

Dopamine Agonists

Drugs like cabergoline or bromocriptine mimic dopamine’s inhibitory effect on prolactin secretion. They are the first‑line treatment for pituitary adenomas and drug‑induced hyperprolactinaemia. Importantly, low‑dose cabergoline has been shown in several studies to lower prolactin without compromising milk supply in most nursing mothers.

Addressing Thyroid Issues

Correcting hypothyroidism with levothyroxine often normalizes prolactin levels within weeks. Because thyroid hormones also influence metabolic rate, treatment can improve overall energy-helpful for exhausted new parents.

Stress Management

Chronic stress raises cortisol, which can blunt dopamine release. Simple techniques-short mindfulness sessions, gentle yoga, or a brief walk with the baby-can help keep prolactin in check.

Support From Lactation Professionals

Even with hormonal hurdles, a lactation consultant can offer practical tips: optimizing latch, increasing feed frequency, and using breast‑compression to stimulate milk flow. These strategies reinforce the natural prolactin‑supply loop.

Quick Reference Table

| Serum Prolactin (ng/mL) | Typical Cause | Effect on Milk Production | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5‑20 (baseline) | Normal non‑lactating state | Insufficient for lactation | Start breastfeeding to boost levels |

| 40‑100 (active lactation) | Physiologic response to suckling | Supports robust milk supply | Maintain frequent feeds |

| 100‑200 (moderate elevation) | Stress, mild hypothyroidism | May cause over‑production or intermittent let‑down | Stress reduction, thyroid screening |

| >200 (high elevation) | Pituitary adenoma, dopamine‑blocking meds | Irregular supply, possible lactation failure | Medical evaluation, possible dopamine agonist |

When to Seek Specialist Care

If any of the following occur, book an appointment with an endocrinologist or a maternal‑health specialist:

- Prolactin >200 ng/mL on two separate tests \n

- Persistent galactorrhoea without a baby

- Headaches, visual changes, or unexplained weight gain

- Failure to establish an adequate milk supply despite optimal feeding practices

Early intervention can prevent long‑term complications, such as bone density loss from chronic high prolactin or the need to wean earlier than desired.

Bottom Line for Nursing Parents

Hyperprolactinaemia isn’t automatically a blocker for breastfeeding. In many cases, the body’s natural rise in prolactin is exactly what you need. The key is to recognize when the hormone has gone too far and to address the root cause-whether that’s a medication, a thyroid issue, or a small pituitary tumor.

With proper medical guidance, most mothers can continue to nurse comfortably while keeping prolactin levels within a healthy range.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can hyperprolactinaemia cause low milk supply?

Yes, especially when prolactin levels exceed 200 ng/mL. Extremely high levels can disrupt the milk ejection reflex and lead to intermittent supply.

Is it safe to take cabergoline while breastfeeding?

Low‑dose cabergoline is considered compatible with nursing in most cases. It quickly lowers prolactin without markedly reducing milk output, but you should discuss dosing with your doctor.

What symptoms suggest a pituitary adenoma?

Headaches, visual field changes (like loss of peripheral vision), and persistent galactorrhoea are classic red flags. An MRI confirms the diagnosis.

Can stress alone raise prolactin enough to affect breastfeeding?

Chronic stress can modestly increase prolactin, usually up to 100‑150 ng/mL. While this may cause occasional let‑down problems, it rarely leads to severe lactation failure without another underlying factor.

Should I get my thyroid checked if I have breastfeeding trouble?

Absolutely. Hypothyroidism is a common, treatable cause of elevated prolactin. A simple TSH test can reveal an under‑active thyroid, and replacement therapy often restores normal lactation.

11 Comments